Opening its gates in 1974, the Riverbanks Zoo & Garden is one of the youngest major zoos in the country - so young that the last of the original zoo animals from its opening day, an

American flamingo, passed away just last year. While the zoo itself is young, the land that it occupies along the Saluda River, weaving its way through South Carolina's capital city, has seen a lot of history. It was the site of a Civil War skirmish (Columbia was one of the cities "visited" by William Tecumseh Sherman on his March to the Sea) and Civil War-era ruins can be seen in the woods along the river.

Being a relatively young facility, Riverbanks has many spectacular exhibits, but the most famous of all is the

Aquarium Reptile Complex, generally known as the ARC. A variety of fish, amphibians, and reptiles are found in a series of themed rooms. In the South Carolina Gallery, aquariums feature trouts and

hellbenders, while terrariums display a varied representation of the Palmetto State's

native snakes... including an impressive selection of

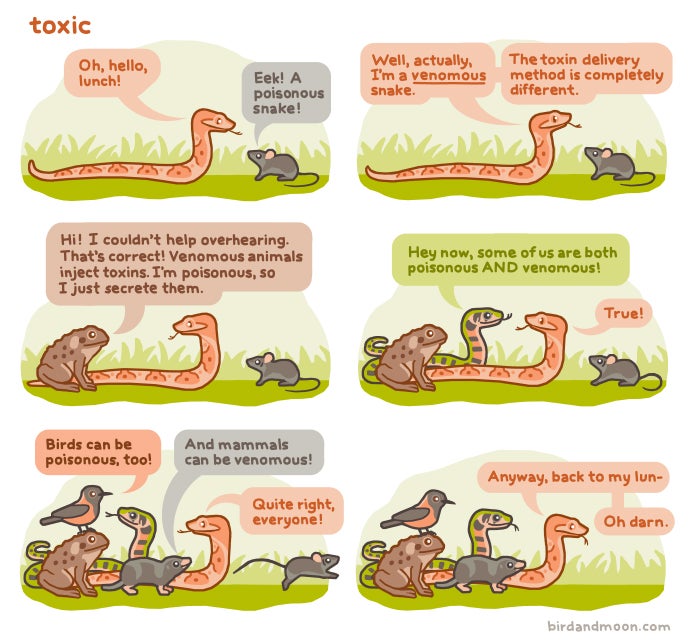

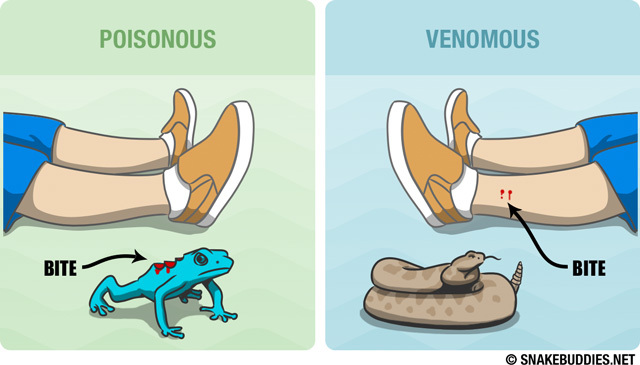

venomous species, such as cottonmouths, timber rattlesnakes, and eastern coral snakes. Alligators occupy a swampy yard elsewhere in the zoo. The Desert Gallery displays yet more hots,

Gila monsters and more rattlesnakes, as well as (at the time of my visit, anyway) baby

Galapagos tortoises and

Grand Cayman iguanas (there are lots of reptiles that I've seen at many zoos but have only ever seen very young specimens here). The hot, humid Tropical Rainforest Gallery features large aquatic displays in a sauna like atmosphere.

Piranhas and arowanas are the most impressive of the fish, but the crowds are more drawn to the big reptiles -

Komodo dragons,

green anaconda, and

tomistoma, all with underwater viewing. The next room features more rainforest reptiles, including an impressive collection of venomous snakes, such as

king cobras, green mambas, and rarely displayed

Mangshan vipers (most impressive to me was

the only elephant trunk snake I've ever seen). From here, visitors enter a darkened aquarium gallery, where reef-sharks, wolf eels, lion fish, and jellies can be seen, along with a massive coral reef display.

The reptile collection was impressive to be sure, but the

Birdhouse at Riverbanks gives it a run for its money. After passing through a flock of American flamingos, visitors enter a gallery surrounded by mixed-species aviaries depicting an Indonesian forest, an African savannah, and a South American clearing. Among the beautiful birds here are

Raggiana birds-of-paradise (I was lucky enough to see a male displaying), Indian pygmy geese, troupials, and wreathed hornbills. The final and most popular display features underwater viewing of various sub-Antarctic penguins. Except for the penguins, held behind glass, the aviaries are behind mesh so fine that it disappears from sight as you watch the birds fly. Scattered across the zoo are more aviaries featuring other birds, including critically endangered

Edwards' pheasants. One particularly cool exhibit features cinereous vultures and Abyssinian ground hornbills perching on a wrecked jeep. Elsewhere in the zoo, the Avian Incubation Center offers a

behind-the-scenes peak at how zoo staff breed and care for endangered birds.

If you asked a non-zoo-nerd visitor who the stars of the zoo are, they'd probably be torn. Many would probably say the

koalas, located in indoor/outdoor enclosures by the entrance of the zoo - even if the sleepy marsupials aren't doing anything, their distinctive eucalyptus/cough-syrup smell will stay with out. Outside, parma wallabies hop in the grassy yard, while lorikeets flit about in a walk through aviary. More Aussie-animal interactions take place at the walk-through 'roo yard, with red kangaroos and

red-necked wallabies.

African animals can also be seen here, whether in the grassland yards, home to giraffe, zebra, and ostrich, or in the new

Ndoki Forest, home to

meerkats, gorillas, and African elephants. The elephant exhibit sloped down from equal level with visitors towards the back to a moat towards the front; when the elephants are at the front of the exhibit, as they were when I was there, visitors are pretty much looking them straight in the eye. Hamadrayas baboons are found in a rocky grotto nearby; a second grotto rotates between lions and

spotted hyenas (with Diana monkeys in the background), while a third houses (admittedly non-African) tigers - these grottos I found to be the least impressive exhibits in the zoo, based on size and complexity. Other exhibits include a pair of

siamang islands, a petting barn area, and a rocky tunnel that leads visitors past a series of small mammal habitats, including two species of lemurs, black-footed cats,

tree kangaroos, and lion-tailed macaques, dubbed the

Riverbanks Conservation Outpost.

There's more to the zoo besides animals, of course, and if you have the time (which I was sadly short on), you should definitely cross the river to view the Gardens which make half of the zoo's name. Alas, all I had time for was a stroll along the woods along the river, which was cool enough, providing some scenic views of the river and the aforementioned ruins.

At the time of my visit, the zoo was preparing to unveil new exhibits for brown bears, river otters, seals, and sea lions, the exhibits for the first two opening this past summer. Riverbanks is already a very impressive facility, an advantage of its youth. Youth fades, however, and what was once new and state of the art can become old and decrepit if allowed to sit still. From what it looks like, Riverbanks has no intention of sitting still. It'll be interesting to watch as the zoo continues to develop and improve.