If there's one thing I like about New Year's Resolutions, it's their testament to the simple fact that none of us is perfect. Within all of us is the potential to do better, whether it's regarding our health, or family life, or our professional life. I have a tendency, perhaps, to oscillate on resolutions. Some years I come up with dozens of them. Other years, zero. Never an in between.

This year coming up is a "dozens" kind of year.

On the first New Year's Eve when I started the blog, I wrote a list of work-related resolutions, part of my continuing effort to be a better keeper.

The thing is, though, only a tiny fraction of the animals under human care in this country are zoo or aquarium animals. There are also lots of lots of pets out there, millions of them. They benefit just as much from training, enrichment, husbandry improvements, and good old fashioned attention as any lion or polar bear. I know that I'm not alone in zookeepers who lavish a lot of attention on their work charges, then come home and do sort of a "good enough" job on their own pets. I'm going to try to change that in 2019.

So my advice this year is that, if you are making resolutions - to lose weight, to quit smoking, to finish a project - try to squeeze at least one more in, this one focused on your pet. Resolve to take your dog for a walk once a day, or get your new cat a new toy every other month, or change your snake's furniture around once in a while. Their happiness and health are in your hands. A little extra attention couldn't hurt.

Search This Blog

Monday, December 31, 2018

Sunday, December 30, 2018

From the News: 22-year old employee killed by escaped lion

22-year-old employee killed by lion that escaped enclosure at animal center: Officials

So I just heard about this, like right this minute. What an unbelievable tragedy. I'm so sorry for the lost keeper and their coworkers. On top of this tragic loss, they also had to see the lion in question destroyed in order to reclaim the body of their coworker. This is every animal care professional's nightmare, and I can't imagine what they must be going through right now

![items.[0].image.alt](https://ewscripps.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/c6c6db8/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1000x563+0+0/resize/1280x720!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fewscripps.brightspotcdn.com%2F74%2F22%2Fb1867aaa479e9bfabce8deaded4a%2Flion-generic.jpg) ...

...Saturday, December 29, 2018

The Hardest Part

The past few months have not been kind to the staff of the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium. What was supposed to have been one of the most joyous experiences possible - the birth of two baby giraffes and a baby Asian elephant - has instead turned to tragedy as all three of the newborns - and one of the mother giraffes - have died. So far, there appears to be no link between the giraffes and elephant (one of the baby giraffes was born via a Cesarean, an inherently risky procedure with giraffes, that tragically proved fatal for mother and calf).

There's seldom any good explanation for why things like this happen, and it can be easy for the caretakers of these animals to feel the heavy burden. Thankfully, the community is rallying to the support of the graving staff, sharing their appreciation for the work that they do and helping them through their losses.

Heartfelt condolences to the giraffe and elephant caretakers at Columbus. Hopefully 2019 is a better year.

There's seldom any good explanation for why things like this happen, and it can be easy for the caretakers of these animals to feel the heavy burden. Thankfully, the community is rallying to the support of the graving staff, sharing their appreciation for the work that they do and helping them through their losses.

Heartfelt condolences to the giraffe and elephant caretakers at Columbus. Hopefully 2019 is a better year.

Rest in Peace

Friday, December 28, 2018

Immersion - You Are Here

The earliest zoo exhibits - like the menageries that predated them - were in the business of transporting the animal to the world of the human, surrounded by bricks and iron and tile and concrete. The Hagenbeck style of zoo exhibit, gaining popularity in the early twentieth century, advocated for presenting the animal in its own world. Towards the end of the century, however, an entirely new school of zoo design made the scene. Like Hagenbeck, its practitioners advocated for displaying the animals within a recreation of their own world. Unlike Hagenbeck, they wanted that recreated world to claim the visitor as well.

Immersion refers to the zoo exhibition style of creating the impression that the visitor is sharing space with the animals in a natural habitat. If going to a traditional zoo could be likened to walking down the halls of an art gallery, looking at the portraits hanging on the walls while knowing that you are totally removed from them - a seascape in one frame, a portrait in another - immersion would be like walking through an outdoor, interactive sculpture garden.

To create an immersive experience, you start off with a natural zoo exhibit, such as Hagenbeck would have envisioned. Then, you extend that natural design into the visitor area. Use the least intrusive barriers between the visitor and the animal to blur the separation between the two. Use the same landscaping - plantings, rocks, etc - in the exhibit and the public area to create the impression that the two areas are blended. Avoid straight lines and right angles - neither exist in nature - instead favoring curves and natural contours. Where non-natural items must be included - such as trash cans, benches, and exhibit signage - disguise them to blend in as seamlessly as possible; a bench could be made to resemble a fallen log, for example, or a trash can a tree stump. Perhaps most importantly, try to isolate the experience. You cannot have an effective immersion exhibit on a busy main path - it needs to be on a side trail, buffered from the noise and commotion of vehicles, large crowds, and concession stands and gift shops. Create a segregated area for an intimate encounter, just the visitor and the animal.

To further develop the experience, seek opportunities to engage all of the sense (well, maybe not taste). Hidden speakers could play natural soundtracks, not only to enhance the experience but to muffle other, unnatural sounds. Sometimes when I clean our parrot exhibit at my zoo, I play a jungle soundtrack as a form of enrichment, and it's hard to deny the soothing impact it can have. Use fragrant plants - pine for a northern forest exhibit, spices for a jungle. Use as much natural material as possible - wood and stone - so that whatever a visitor touches when the grasp a railing or touch a fence post feels like it belongs there. Even the path itself can aid in the experience - use mulch or stone dust or crusher or hard-packed dirt over concrete and macadam.

This may seem like a lot of work for no obvious benefit. Still, I believe that there is real value in immersing visitors in the environment of the animals. It can led to a subtler, deeper appreciation for the animal and its place in the environment. It has been demonstrated that the manner in which an animal is displayed can have a discernible impact on how the visitor perceives it - dangerous, stupid, boring, brooding? Or imposing, majestic, beautiful? Such perceptions, in turn, can influence how likely a visitor is to support the conservation of that species.

A little planning and a few minor touches when designing a new exhibit, it seems, can make a big difference.

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Zoo History: Hagenbeck Comes to America

Recent decades have seen tremendous innovation in the techniques and technologies that zoos use to display their animals. There are exhibits with underwater viewing, providing exciting new vantage points for penguins, otters, crocodilians, polar bears, seals, and hippos. There are walk-through exhibits, originally primarily for birds, but now also featuring kangaroos, lemurs, and other species. There is super-strong glass and barely-visible mesh, allowing nearly unobstructed views of animals up close. There is also (to my intense skepticism) reverse lighting, which theoretically allows for nocturnal viewing of nighttime animals, which in my experience never seems to really work.

All of these new methods, revolutionary at the time of their development and introduction, have since been replicated over and over again by zoos around the globe. At the time of unveiling, each is considered to be the latest, greatest new idea in zoo design. At the end of the day, however, all are simply variations of a single idea, which isn't even that new. It's the idea that the optimal way to display wild animals in a zoo setting is by trying to replicate their natural environment.

The visionary behind that concept was the German animal dealer, Carl Hagenbeck Jr., who put the theory into practice when he opened his own zoo near Hamburg, Germany. Hagenbeck's zoo was a hit, and today he is considered the pioneer of modern zoo design. As is often the case with revolutionary new ideas that today are accepted and taken for granted everywhere, we tend to gloss over the fact that, at the time, a lot of respected voices in the profession considered his ideas to be heresy. Carl certainly didn't have too many fans in the good ol' US of A.

Resistance to the innovative new zoo exhibits was largely driven by the eminence grise of American zoos, the brilliant - if irascible - William T. Hornaday, the veritable founder of the Smithsonian National Zoo and then the director of the Bronx Zoo (a name that he loathed, insisting upon "the gardens of the New York Zoological Society"). Hornaday was adamant that "the Hagenbeck fad [which] has inoculated some half-baked western zoo-makers" was an abomination that needed to be stomped out. In his opinion, larger, more natural zoo exhibits were counterproductive for what he saw as the primary goal of the zoo - allowing scientists to study animals. They put the animal too far away for the scientists to observe, and the moats that they required ate up lots of valuable space that could be better put to other purposes - such as housing more animals. In many ways Hornaday was one of the most progressive zoo directors in America - it was he who first saw the role of zoos supporting conservation of animals in the wild - but on this point (on a lot of points, actually) he was obstinate.

Part of his opposition, to be sure, was based on principle. Other parts, however, seemed to be driven by racial prejudice. Hornaday had been a tremendous fan of Hagenbeck, corresponding with him regularly - but that was before World War I. Afterwards, Hornaday developed a bitter grudge against the German people, to such an extent that he cancelled the Zoo's subscriptions to all German journals and professional literature (the Society's board overruled him on this). In his mind, natural zoo exhibits were a diabolical invention of the Hun, and to utilize them was to admit German supremacy over America in the eyes of the world. And whenever William T. Hornaday made up his mind about something, it was almost impossible to change it.

Whenever colleagues wrote to him for advice as to whether or not they should build new "Hagenbeck" exhibits, Hornaday remain very opposed. Still, a few resisted. The first resistance popped up in the Denver Zoo, where a bear exhibit opened in 1918. A few years later, Saint Louis Zoo, having written to Hornaday for advice on the subject and then decided to disregard it, opened a series of bear exhibits (bear exhibits were popular prototypes for "natural" exhibits because they largely consisted on towering rock formations, which looked very impressive. To be fair, most of these early "natural" bear exhibits were not very good at providing a habitat that facilitated natural behavior for the animals, but they did look good on postcards).

Hornaday scoffed, claiming "the Saint Louis Zoological Society is making a great mistake in putting all its money into costly piles of rock and concrete to shelter far distant animals." Looking back from 2018, I think the St. Louis Zoo would disagree. Having just moved their Andean bears and polar bears into new exhibits, the zoo has renovated the bear dens - preserving the original rockwork - into a massive new habitat for grizzly bears.

To Hornaday's undying ire, after his retirement, his own successor, Dr. Reid Blair, decided to dabble with Hagenbeck's exhibit style. To this day, the Bronx Zoo boasts of a lovely African Plains exhibit, where lions overlook a herd of peacefully grazing nyala antelope. Decades later, it still stands - surrounded by a host of other open, natural enclosures, many utilizing technological components that would have seemed like magic at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Sometimes, it can be slightly difficult to see some of the animals. What you can see, however, is often beautiful, and with the added space and natural features, it's possible for a student or scientist to learn a lot more about animal behavior and biology than would be in a small, sterile room at close range. So yeah, given a chance to warm up to it, I think that Hornaday would have approved (although I doubt that he would even for a second have conceded that he was wrong).

All of these new methods, revolutionary at the time of their development and introduction, have since been replicated over and over again by zoos around the globe. At the time of unveiling, each is considered to be the latest, greatest new idea in zoo design. At the end of the day, however, all are simply variations of a single idea, which isn't even that new. It's the idea that the optimal way to display wild animals in a zoo setting is by trying to replicate their natural environment.

The visionary behind that concept was the German animal dealer, Carl Hagenbeck Jr., who put the theory into practice when he opened his own zoo near Hamburg, Germany. Hagenbeck's zoo was a hit, and today he is considered the pioneer of modern zoo design. As is often the case with revolutionary new ideas that today are accepted and taken for granted everywhere, we tend to gloss over the fact that, at the time, a lot of respected voices in the profession considered his ideas to be heresy. Carl certainly didn't have too many fans in the good ol' US of A.

Resistance to the innovative new zoo exhibits was largely driven by the eminence grise of American zoos, the brilliant - if irascible - William T. Hornaday, the veritable founder of the Smithsonian National Zoo and then the director of the Bronx Zoo (a name that he loathed, insisting upon "the gardens of the New York Zoological Society"). Hornaday was adamant that "the Hagenbeck fad [which] has inoculated some half-baked western zoo-makers" was an abomination that needed to be stomped out. In his opinion, larger, more natural zoo exhibits were counterproductive for what he saw as the primary goal of the zoo - allowing scientists to study animals. They put the animal too far away for the scientists to observe, and the moats that they required ate up lots of valuable space that could be better put to other purposes - such as housing more animals. In many ways Hornaday was one of the most progressive zoo directors in America - it was he who first saw the role of zoos supporting conservation of animals in the wild - but on this point (on a lot of points, actually) he was obstinate.

This exhibit - currently housing coatis, previously monkeys - is part of the bear grottos of the Denver Zoo.

Whenever colleagues wrote to him for advice as to whether or not they should build new "Hagenbeck" exhibits, Hornaday remain very opposed. Still, a few resisted. The first resistance popped up in the Denver Zoo, where a bear exhibit opened in 1918. A few years later, Saint Louis Zoo, having written to Hornaday for advice on the subject and then decided to disregard it, opened a series of bear exhibits (bear exhibits were popular prototypes for "natural" exhibits because they largely consisted on towering rock formations, which looked very impressive. To be fair, most of these early "natural" bear exhibits were not very good at providing a habitat that facilitated natural behavior for the animals, but they did look good on postcards).

Hornaday scoffed, claiming "the Saint Louis Zoological Society is making a great mistake in putting all its money into costly piles of rock and concrete to shelter far distant animals." Looking back from 2018, I think the St. Louis Zoo would disagree. Having just moved their Andean bears and polar bears into new exhibits, the zoo has renovated the bear dens - preserving the original rockwork - into a massive new habitat for grizzly bears.

These grizzly bears at the St. Louis Zoo are in the old exhibit which predates the current one, but the rockwork in the background - the original from the early twentieth century - has been saved and incorporated into the new habitat.

Sometimes, it can be slightly difficult to see some of the animals. What you can see, however, is often beautiful, and with the added space and natural features, it's possible for a student or scientist to learn a lot more about animal behavior and biology than would be in a small, sterile room at close range. So yeah, given a chance to warm up to it, I think that Hornaday would have approved (although I doubt that he would even for a second have conceded that he was wrong).

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Merry Christmas!

Merry Christmas to everyone! Hopefully you find whatever it is that you wish for under the tree... thirty years later, I'm still waiting for that damned hippo...

Monday, December 24, 2018

The Day Before Christmas at the Zoo

"Twas the day before Christmas, and all through the zoo,

The keepers were bustling, with too much to do.

There were diets to prep, and nest boxes to hay,

All to finish early, and head home Christmas Day."

Santa and his reindeer aren't the only ones in a hurry Christmas Eve. Every zoo and aquarium that I have ever worked at has been closed on Christmas Day. Of course, the animals don't particularly care and want to get fed anyway, the ungrateful bums, which puts us in line with police, firefighters, and a host of other folks who have to work on the morning of December 25th. Unlike a lot of those other guys, we have the option of wrapping up early.

December 24th is the day for getting ready, for making sure that the next day is a short day. I've got my diets for all of my animals tomorrow already prepared and in the fridge - with the exception of a few which I have learned from experience don't keep super well overnight. I gave most of my enclosures a second cleaning right before I left. Some of them can go a day without cleaning tomorrow. Others will be that much simpler to finish in a hurry. Enrichment for tomorrow is going to be brief, all stuff that requires very little assembly time. As kids get a day off from school, so will the animals get a day off from training.

Supplies are stocked up, feeders are topped off, basically anything that can get done in advance, I've done.

Which is kind of silly, upon retrospect. I actually don't have anything else to do tomorrow. I'll be celebrating Christmas a few days later.

So after all this rushing and prepping, I think I might end up... loitering at the zoo. Once all of my coworkers have zipped out the door, I'll probably stroll around. It's not often that I have the zoo to myself (in daylight, anyway) and it's a fairly mild winter. Just a quiet walk around with the animals, just me and them... that might be one of the best Christmas presents to myself that I could ask for.

Merry Christmas (Eve)

Saturday, December 22, 2018

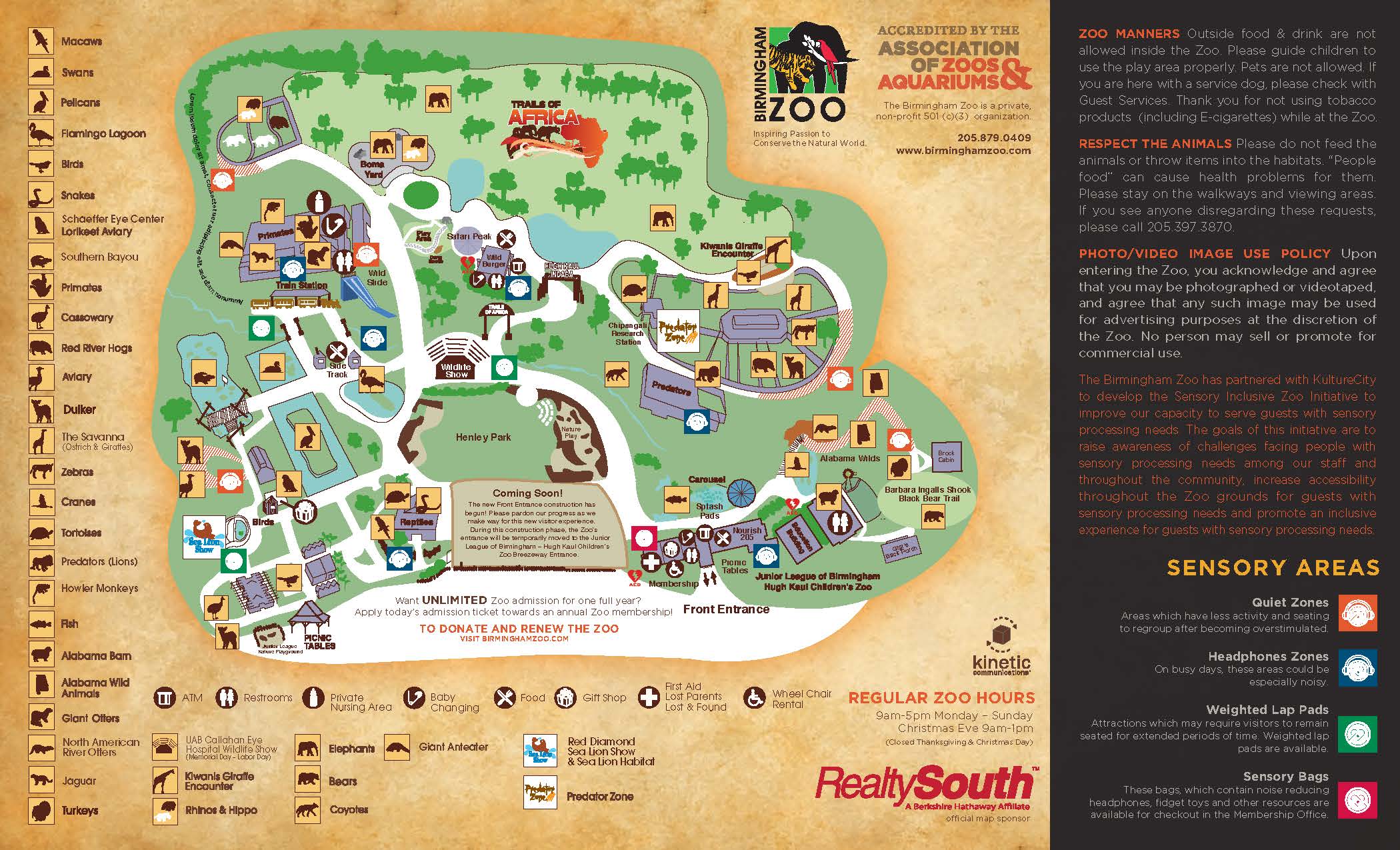

Mapping It Out

"Our brain is mapping the world. Often that map is distorted, but it's a map..."

- E. O. Wilson

Specifically, I wish that there had been a map.

From an early age, I have loved to collect zoo maps. I would take one from every visit to the zoo; family members who were traveling out of town would often swing by the zoos that they passed just to pick up a copy to bring back for me. I kept them in a little file cabinet that I had scavenged for that purpose, periodically taking them out to look at.

In the pre-Internet days, they provided one of the easiest ways to know what animals - or at least what major animals - a zoo housed. It also provided interesting information as to how the animals were displayed and arranged - by what theme, in what mixed-species combinations, in approximately what-sized enclosures. From collecting maps from the same zoo over the years, I was able to trace the evolution and development of their facilities, watching as they transitioned from small enclosures arranged by taxonomic groupings to large, geographically-themed habitats.

When I first began to develop my interest in zoo design, it largely took the form of maps. I'm a terrible artist - I could visualize the habitats that I wanted to create, down to the intricacies of the rock work and water features, but I couldn't draw them worth a damn, and the resultant efforts just frustrated me. Instead, I would doodle out maps of my dream zoos - the placement of paths, the order that the animals would be encountered in, the hiding of service structures and holding buildings. Upon further reflection, the detail and attention that I lavished on these projects might have had something to do with my lackluster scholastic performance in middle school... I found zoo design to be a much better use of fifth period than I did Algebra II.

When I moved away from home after college, I drove across the country to start my first full-time zoo job. I turned that drive into a zoo-seeing trip; combined with all of the zoos that I visited once I arrived in my new city, I amassed quite a collection of new maps. In my new apartment, over a thousand miles from anyone that I knew outside of my new job, these maps were the art for my new home. Lacking the budget (or, to be honest, the inclination) for much else in the way of decorating, I plastered the walls with maps and guidebooks from the new facilities I had visited.

Today, all of this is on the Internet, of course, to the point that, when planning to visit a new facility, I usually have a zoo's layout committed to memory before I hit the turnstile. Which isn't to say I don't take a map, of course.

I still have some bare spots on my walls.

Friday, December 21, 2018

Book Review: The Zoo: The Wild and Wonderful Tale of the Founding of the London Zoo

"In these five acres something very different was demanded. It was rather more like landscape gardening, he mused. Or even town planning, with the proviso that he was building for birds and beasts rather than humans. No, he corrected himself, that was not true. The challenge was to create an environment where humans could comfortably, elegantly, enjoyably observe the creatures. Of course he was building for mankind, rather than for beasts."

This was not always in the case.

In the beginning of the modern zoo era was the Jardin des Plantes, born from the ruin of the French royal menagerie at Versailles. Perhaps the first true modern zoo, however, could be said to have been born across the Channel in London - the Gardens of the Zoological Society of London, popularly known as the London Zoo. Looking back at this institution and the age at which it was constructed, it seems highly improbable that such a facility could ever have arisen. And it was.

Isobel Charman tells the story of the birth of the Zoological Society of London in, The Zoo: The Wild and Wonderful Tale of the Founding of the London Zoo: 1826-1851. It was one of the two finest histories of the Zoo in Regent's Park, the other being Wilfred Blunt's The Ark in the Park. The two books vary in two important details, however. The first is scope. While Blunt's work focuses on the whole of the nineteenth century, Charman limits her story to the early founding days of the Zoo, focusing on the times when it seemed that it surely must crash and burn (sometimes literally). The second difference is in the telling. Charman uniquely frames her story from the perspective of seven individuals who have shaped the history of the park, from its founding visionary Sir Stamford Raffles (a busy man who was also responsible for the founding of modern Singapore) to the 13th Earl of Derby, who's seemingly quixotic quest for a hippopotamus may very well have been what saved the young zoo. Among the other luminaries features is an unassuming naturalist named Charles Darwin, for whom the animals in the Zoo were in some ways equally important to his theorizing about evolution as were the finches of the Galapagos.

If Charman's book were a work of fiction - and therefore you didn't already know how the story was going to end, more or less - you would swear that there was no way that there would be a happy ending. The book is largely one long catalogue of disaster, punctuated by a few minor successes, before sinking back into despair. Animals die in great quantities. Staff members don't know what they are doing. Attendances sinks to new lows, threatening the future of the park. More animals are brought in to try and boost attendance. The staff doesn't know what they are doing, so they die. Repeat. Meanwhile, they face constant competition from a rival zoo popping up across town, run by Mr. Cross, an infamous former menagerie-owner who seeks respectability at the expense of the London Zoo.

If anything, the sad fates of the animals - many of whom seem to be headed for the taxidermist as soon as they arrive - were some of the most intriguing. It really shouldn't but it's still so surprising to me to read about how difficult it proved for the fellows of the ZSL - ostensibly some of the finest scientific minds of their age - to keep alive some animals that we now consider to be extraordinarily easy to maintain and breed. I mean, folks in Texas trailer parks can easily keep tigers, breed them even, but they drop like flies in the world's first scientifically run zoo?

There's a lot to be said about being "the first," I suppose, and part of that is that you get to be the first one to make all of the new mistakes. There were parts of The Zoo that I found almost cringe-worthy for those reasons. I just wanted to climb into the book and shout, "You idiots, you're doing it all wrong!" If I had lived at the time, I might very well have begged them to give up the whole enterprise, seeing the sacrifices of animals as unworthy for whatever goal they thought they were working towards.

I'm glad they didn't. London and Paris - followed by Philadelphia, Berlin, and other early modern zoos - created the foundation of the modern zoo, zoos that would go into directions that these early pioneers never dreamt of. Who would imagine back in the mid-1800s that a day would come when, instead of plucking animals from the wild (with massive casualties) we would be reintroducing species back there? That we would be breeding species - with regularity - that were considered impossible to keep alive back then. That instead of crude stone sheds, we would see some animals in enormous free-flight aviaries, aquarium tanks of millions of gallons of water, or paddocks acres in size.

If our zoos and aquariums have grown into something new, something special, and we feel inclined to look down our noses at our progenitors, who should remember - we have only seen this far because we've stood on the shoulders of giants. Sure, giants who might have stumbled and blundered around a bit. But giants nonetheless, who are still standing today.

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

Single Large, or Several Small?

With the onslaught of human expansion around the globe, finding patches of habitat for animals to remain in the wild (such as it is) is proving to be increasingly difficult. Conservationists are scrambling to preserve what little habitat remains, which in some cases requires buying it outright. In these situations, they are often faced with the challenge of answering the question of SLOSS - Single Large? Or Several Small? Is it better to establish one large new reserve, which could hold larger, more sustainable populations of different species? Or is it best to go for several smaller ones, opting not to put all of your eggs in one basket and protect several disparate patches of habitat.

Think about it like this - if you were in charge of planning protected areas for the United States of America, would it be best to have a small park in each of the fifty states? Or to say, "Okay, Montana is off limits" and sacrifice the rest?

I've often encountered a different version of the SLOSS question, this one pertaining to zoos.

Most zoos - and virtually all aquariums - are landlocked. This is especially true of the older, urban zoos, typically built in the hearts of the cities. The chance to expand outward is often limited or nil - that's a major reason behind the establishment of the Conservation Centers for Species Survival program. But what to do with the land inside the zoo itself? Is it best to do a small number of very large enclosures, or to do as many small ones as you can fit? The first option can provide picturesque, spacious enclosures that visitors will love (size = welfare in the eyes of many zoo visitors). The second can allow for a tremendous amount of diversity. On a small scale, imagine that you were given responsibility for a new reptile house construction project. Should you try to incorporate as many diverse animals as possible in separate enclosures, which would be of tremendous value to conservation programs? Or, you could say "This half of the building is for Komodo dragons, this half is for crocodiles, and we're done."

Large exhibits have their advantages. They give you room to house more individuals of a species - instead of three zebras, you can have an actual herd. That gives you more benefits in the form of social interaction, mate choice, and the expression of natural behavior. It makes it easier to introduce mixed-species occupants to an enclosure. Animals have the option of getting further away from the public, enjoying some privacy. Visitors feel better seeing animals with more space.

Having many smaller enclosures, on the other hand, can also give you a lot more flexibility. Suppose you have an animal or a species that's not getting along or doing well with its exhibit-mates, say a bird that's getting beaten up by other birds in the aviary (and even in a massive free-flight aviary, bully birds will always be able to find that one bird they want to pick on). It would be nice to have the option of having a separate enclosure that this bird/species can be relocated to for its own good and comfort. Likewise, you can have more flexibility with separating animals for breeding, introductions, raising of young, and medical purposes. Many zoo breeding programs are also limited by the amount of space that is available for the next generation of animals. Having more enclosures means more animals can be housed in a zoo or aquarium.

Perhaps the best - if most complicated - version is to go with some variation of both. It would be great to have the largest enclosures that are practical/possible (not always the same thing) that could be segregated as needed into separate components. For example, an African exhibit that could consist of yards of zebra, antelope, ostrich, and giraffe, which could be opened up into one large habitat when the opportunity is available, but separated as needs be. If the antelope, for example, are having calves, they could be isolated in their enclosure - comfortable and spacious enough for them - but kept protected from the zebras, the males of which sometimes have a homicidal fascination with baby antelope. If a new giraffe arrived at the zoo, it could be introduced to the other species one at a time instead of being flung into a whole mess of other animals in one go.

There are constant new ideas and innovations that go into the design of optimal habitats for zoo and aquarium animals, and members of the field are constantly striving to create new ones. It's a far cry from the earliest days of modern zookeeping, where the only considerations that an enclosure had to satisfy were could people see the animal and could the animal escape. We've certainly come a long way, but there's much further still to go...

Think about it like this - if you were in charge of planning protected areas for the United States of America, would it be best to have a small park in each of the fifty states? Or to say, "Okay, Montana is off limits" and sacrifice the rest?

I've often encountered a different version of the SLOSS question, this one pertaining to zoos.

Most zoos - and virtually all aquariums - are landlocked. This is especially true of the older, urban zoos, typically built in the hearts of the cities. The chance to expand outward is often limited or nil - that's a major reason behind the establishment of the Conservation Centers for Species Survival program. But what to do with the land inside the zoo itself? Is it best to do a small number of very large enclosures, or to do as many small ones as you can fit? The first option can provide picturesque, spacious enclosures that visitors will love (size = welfare in the eyes of many zoo visitors). The second can allow for a tremendous amount of diversity. On a small scale, imagine that you were given responsibility for a new reptile house construction project. Should you try to incorporate as many diverse animals as possible in separate enclosures, which would be of tremendous value to conservation programs? Or, you could say "This half of the building is for Komodo dragons, this half is for crocodiles, and we're done."

Large exhibits have their advantages. They give you room to house more individuals of a species - instead of three zebras, you can have an actual herd. That gives you more benefits in the form of social interaction, mate choice, and the expression of natural behavior. It makes it easier to introduce mixed-species occupants to an enclosure. Animals have the option of getting further away from the public, enjoying some privacy. Visitors feel better seeing animals with more space.

Having many smaller enclosures, on the other hand, can also give you a lot more flexibility. Suppose you have an animal or a species that's not getting along or doing well with its exhibit-mates, say a bird that's getting beaten up by other birds in the aviary (and even in a massive free-flight aviary, bully birds will always be able to find that one bird they want to pick on). It would be nice to have the option of having a separate enclosure that this bird/species can be relocated to for its own good and comfort. Likewise, you can have more flexibility with separating animals for breeding, introductions, raising of young, and medical purposes. Many zoo breeding programs are also limited by the amount of space that is available for the next generation of animals. Having more enclosures means more animals can be housed in a zoo or aquarium.

Perhaps the best - if most complicated - version is to go with some variation of both. It would be great to have the largest enclosures that are practical/possible (not always the same thing) that could be segregated as needed into separate components. For example, an African exhibit that could consist of yards of zebra, antelope, ostrich, and giraffe, which could be opened up into one large habitat when the opportunity is available, but separated as needs be. If the antelope, for example, are having calves, they could be isolated in their enclosure - comfortable and spacious enough for them - but kept protected from the zebras, the males of which sometimes have a homicidal fascination with baby antelope. If a new giraffe arrived at the zoo, it could be introduced to the other species one at a time instead of being flung into a whole mess of other animals in one go.

There are constant new ideas and innovations that go into the design of optimal habitats for zoo and aquarium animals, and members of the field are constantly striving to create new ones. It's a far cry from the earliest days of modern zookeeping, where the only considerations that an enclosure had to satisfy were could people see the animal and could the animal escape. We've certainly come a long way, but there's much further still to go...

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Species Fact Profile: Northern Luzon Giant Cloud Rat (Phloemyx pallidus)

Northern Luzon Giant Cloud Rat

Phloeomyx pallidus (Nehring, 1890)

Range: Northern and Central Luzon Island (Philippines)

Habitat: Lowland and Montane Tropical Forests, up to 2200 Meters

Diet: Leaves, Fruits

Social Grouping: Pairs

Reproduction: Most information from captivity. Appear to bred year round. Single young per year, born in a tree cavity or hole in the ground. Female carries the infant.

Lifespan: 12 Years

Conservation Status: IUCN Least Concern

- Total length 70-77 centimeters, with 30-32 centimeters of tail. Weigh 2-2.6 kilograms.

- Large, blunt head has small ears and long whiskers. Feet and hands are large, adaptations for climbing, while the tail is fully furred

- Fur is long and somewhat rough, usually a combination or white or pale gray/yellow with dark brown or black markings on the face or body. Some specimens are pure white, others pure black or brown. Fur in some captive specimens is sometimes reddish

- Nocturnal, primarily arboreal, but may come downt o the forest floor, where it moves slowly

- Locally common within its range, but in decline due to habitat loss to commercial logging and agriculture. Shows some tolerance for disturbed habitat, such as plantations (will raid crops). Protected legally, but hunting is allowed by indigenous peoples using traditional hunting methods

Saturday, December 15, 2018

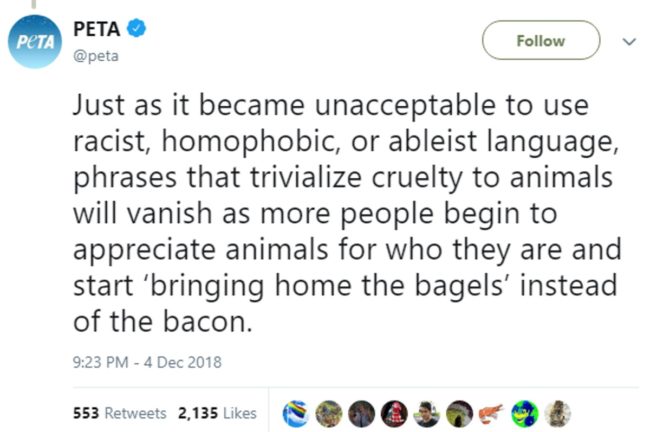

Words with Friends (... and PETA)

Jeez, you'd think PETA - the self-proclaimed People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals - would have bigger fish to fry. The Norfolk-based Animal Rights group came out recently with new phrases that it wants to introduce to our lexicon to replace what it believes are anti-animal sayings. Let's not mince words. These are stupid. Not only do they sound unnatural and inauthentic, but some of them don't even make sense. To kill two birds with one stone is an impressive, or at least difficult, accomplishment in terms of aim and skill. Two feed two birds with one scone... not so much. I mean, unless we're talking about ostriches here. You could probably feed a dozen birds with one scone. Not that I would recommend it, though, because it would be unhealthy for the birds.

I will admit, in recent years I've developed a dislike for people using the word "zoo" to denote a chaotic, crazy situation. I can't say I would tie myself into such ridiculous linguistic knots to avoid it, but there is that.

There's been a lot of mockery of this in the press, as with most things PETA does. So, in a sense, I guess their marketing team is kind of brilliant. They got a whole lot of free press over this. Most of it's bad, mind you, and brings to mind lots of peoples' favorite anti-PETA stories such as the high kill rates at their shelters, but hey, any publicity is good publicity... right?

Friday, December 14, 2018

American Humane Association Accreditation

Just recently, Busch Gardens, the Tampa amusement park and zoo, announced that its animal facilities had been accredited by the American Humane Association (not to be confused with the Humane Society of the United States). You might know AHA as the organization that posts in the credits of movies that no animals were harmed in the production of the film. AHA is now turning their eye on zoos and aquariums, offering facilities a chance to secure the title of "Certified Humane."

I'm still not 100% sure what to make of this. On the one hand, it seems like a lot of extra paperwork considering that my facility (and almost all of the facilities that I've reviewed on this blog) is already accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, generally considered to be the most rigorous, stringent reviews available to zoos and aquariums in this country. What's another few letters on the institutional resume really worth?

On the other hand, I can see some advantages. For one thing, AHA accreditation looks solely at animal care and welfare; AZA accreditation looks at that, to be sure, but also at every other aspect of the zoo, from staff salaries (*cough*) to education programs to support of conservation programs. AZA membership also comes with a price, so I could imagine that smaller, less well-funded zoos might be open to the idea of getting this certification to demonstrate their commitment to animal welfare, even if they can't afford to join AZA.

What I'm torn about is an accrediting body that's not made of zoo and aquarium folks. I wonder, do they really know what they are talking about (I'm not being facetious, I just don't know - I've encountered remarkably few people who know anything about the welfare of exotic animals under human care except for those who actually do it). That being said, a critique that anti-zoo folks sometimes lobby at zoos is that they police themselves - that we are supposed to accept that some zoos are good just because other zoos say that they are. Perhaps having an outside force that has less skin in the game would be advantageous, if only for credibility's sake.

I don't imagine anyone dropping AZA-membership just to get this, and I'll admit, I think I'll wait a while longer to see how much of a thing this AHA-accreditation ends up being before I decide to look at membership or not. Despite my skepticism, it could always be said that more oversight and transparency can always be beneficial. It can help us remain focused on improving our standards, while also reassuring our communities that the animals remain our top priority.

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Zoo Review Updates

Writing so much over the last few days about building my dream exhibits (or learning to patch up the ones I have), it seemed like as good of a time as any other to check in and see what new exhibits have opened up at zoos we've previously visited:

Zoo New England's Stone Zoo has opened Caribbean Coast. To the sound of steel drum music, visitors meander past flamingos, macaws, and critically endangered Jamaican iguanas. The biggest crowd pleasers, however, are the seldom-displayed South American bush dogs.

Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo has just opened a red panda exhibit, and hopes to open a spider monkey exhibit in the spring. The big project on the horizon, however, is the planned new home for Amur tigers - the Zoo had cubs recently and is need of more living space.

The Amur leopard and snow leopard exhibits at the Turtle Back Zoo just got a face lift. With the Zoo's African penguins relocating to the new African area, the slate was cleared at the Zoo's entrance for a new habitat of American flamingos.

Elmwood Park Zoo has added mountain zebras to its giraffe exhibit, continuing its slight branching out from North and South American species.

The National Aviary has completely refurbished its oldest exhibit, The Rainforest, with a new roof to let more light in, a 15-foot waterfall, and other features. Among the 100-odd birds calling the renovated room home are hyacinth macaws, Guam rails, and Victoria crowned pigeons.

Maryland Zoo in Baltimore is in the midst of a renovation of its African Journey, making major renovations and expansions to the habitats of three of Africa's most iconic mammals - African elephants, giraffes, and lions. The elephants are getting a greatly expanded habitat, swallowing some empty exhibit space that's been vacant since the African penguins moved to their new habitat. I'll be a little sad to see the end of Rock Island - the exhibit, as unimpressive as it looked, had a huge role in the Zoo's history - but it'll be great to see their elephants with so much more room to roam.

The National Aquarium in Baltimore has furthered its commitment to animal care with the opening of a new facility for quarantine, holding, and special care, the Animal Care and Rescue Center. While not a part of the main facility, it will still be open to visitors on special tours.

National Zoo is still plugging away at their new bird house, Experience Migration, but at the same time is working on fixing up single-species exhibits through the Zoo. This year saw a fancy new home for naked mole rats in the Small Mammal House, complete with a behind-the-scenes view of the tunneling rodents. Next up is a new home for one of the zoo world's earliest conservation success stories (yet one little-heard of by the public) - the Przewalski's wild horse. This is especially great news due to the role that National Zoo's sister facility, the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, has played in the conservation of this species.

The big news at Virginia Zoo is the opening of the new World of Reptiles. It's an incredible upgrade over the old building. Passing by the giant viper sculpture guarding the entrance, visitors will encounter a host of exciting species, including an impressive assortment of venomous snakes and monitor lizards. Not all of the occupants are reptiles or amphibians - two species of monkey are also found inside, along with two-toed sloths, goliath bird-eating spiders, and lined sea horses. The stars are the Siamese crocodiles - the first ever to be displayed at the Zoo - in an exhibit complete with underwater viewing.

Sylvan Heights Bird Park opened a wonderful saddle-billed stork aviary. Often featured in hoofed mammal exhibits, these birds only breed in aviary settings, so hopefully the Park will be boasting chicks in the near future!

Jacksonville Zoo opened up its new African Forest, a spacious new home for gorillas, bonobos, mandrills, and other African primates. The centerpiece of the exhibit is an enormous artificial tree, from which keepers can have access to the animals at all levels of the exhibit. This allows the staff to provide enrichment and training opportunities up high, encouraging the animals to climb and spend more time exploring the upper-reaches of their exhibit. A small new manatee hospital has opened in the Zoo's Florida area, allowing visitors to watch as Jacksonville Zoo staff rehabilitate injured manatees for release back into the wild.

St. Augustine Alligator Farm unveiled the new Oasis on the Nile, a new habitat for Nile crocodiles. This Egyptian-themed enclosure used artifacts and décor to celebrate the role that Africa's largest reptile had in the culture and religion of Ancient Egypt. It's such an awesome exhibit that a local idiot decided that he had to jump into it recently, with predictable results.

Brevard Zoo is working on an aquarium building. The Zoo also recently took in a pair of non-releasable black bears.

Detroit Zoo also just opened a massive new habitat for red pandas. The fiery-red pandas can be viewed in part from an 80-foot rope bridge that extends along the enclosure. The red pandas aren't the only East Asians to get fancy new digs at the Zoo, as a new, room-sized habitat for Japanese giant salamanders was opened in the amphibian house, replacing what was already one of the better exhibits I've seen for the species. A new exhibit for tigers is next on the agenda.

Phase One of Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo's Asian Highlands has opened. The first phase includes Indian rhinoceroses, red pandas, two species of Asian deer, and white-naped cranes. Tigers, snow leopards, sloth bears, gorals, and takin will follow next year in Phase Two. After that, there is much more renovation and expansion ahead. The Zoo's old cat complex is now empty, as are the bear dens. A new sea lion exhibit is in the works.

For years, San Diego Zoo has been known for having one of America's best collections of Australian wildlife. Now, it's sharing the wealth with its sister facility, the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. Matschie's tree kangaroos, wombats, and cassowaries are among the species being featured in Walkabout Australia. The exhibit includes a walk-through habitat of grey kangaroos and red-necked wallabies.

On top of all of this, a host of zoos - including North Carolina Zoo, Cincinnati Zoo, Albuquerque BioPark Zoo, Brandywine Zoo, and Potawotami Zoo have all unveiled new master plans, with big hopes for exciting new exhibits. I can't wait to start revisiting some of these zoos to see what new surprises are in store.

Monday, December 10, 2018

Design on a Dime

I've spent a lot of idle time dreaming up my perfect zoo exhibits. You'd think that would result in me having some awesome exhibits of my own... but you'd be wrong.

The problem with having a very active, elaborate imagination is that sometimes it becomes too easy to lose yourself in it. You get so caught up with what could be or should be in your mind's eye that you lose sight of what is, and, more importantly, what you have the potential to actually do. You fall so in love with your ideal design that your immediate reaction to tear the old, existing one down and start from scratch and, lacking the ability or funds to do that, you do nothing.

I'm bad at this. My boss is even worse.

I blame it on his big-zoo background, to be honest. He's spent most of his career at giant zoos with giant budgets, so in his mind every new construction, every renovation is a multi-million dollar production number with enough gunite rockwork to make a concrete Mt. Everest, at least two waterfalls, and that fancy electronic signage that never seems to work after the first week.

The rest of the staff is on the other side of the room going, "I was thinking a fresh coat of paint and some new fill dirt."

I'm in between.

The fact is, we all want the big renovation with huge new spaces, lots of new features, and attractive landscaping that our animals love. It can take a long time to plan and fundraise for that, however, and there are more than a few animals I've seen in substandard enclosures, waiting for the day it all comes together. The truth is, you can make a big positive difference for your animals in their enclosure without spending lots of money.

The problem with having a very active, elaborate imagination is that sometimes it becomes too easy to lose yourself in it. You get so caught up with what could be or should be in your mind's eye that you lose sight of what is, and, more importantly, what you have the potential to actually do. You fall so in love with your ideal design that your immediate reaction to tear the old, existing one down and start from scratch and, lacking the ability or funds to do that, you do nothing.

I'm bad at this. My boss is even worse.

I blame it on his big-zoo background, to be honest. He's spent most of his career at giant zoos with giant budgets, so in his mind every new construction, every renovation is a multi-million dollar production number with enough gunite rockwork to make a concrete Mt. Everest, at least two waterfalls, and that fancy electronic signage that never seems to work after the first week.

The rest of the staff is on the other side of the room going, "I was thinking a fresh coat of paint and some new fill dirt."

I'm in between.

The fact is, we all want the big renovation with huge new spaces, lots of new features, and attractive landscaping that our animals love. It can take a long time to plan and fundraise for that, however, and there are more than a few animals I've seen in substandard enclosures, waiting for the day it all comes together. The truth is, you can make a big positive difference for your animals in their enclosure without spending lots of money.

- Add new natural substrates, appropriate for the animal and its habitat. It may be sand, soil, mulch, gravel, or some combination thereof (the later is ideal, really - it lets your animal have choices and variety). Even the most barren enclosure can be freshened up with new substrate, which can allow the animal to dig, bury things, build nests, dust bath, tunnel, or whatever else it wants to do. Hard substrates can help hoofed mammals wear down their hooves. Soft substrates can prevent sensitive feet from becoming abraded.

- Install perching and furniture. Browse-hungry hoofstock keepers aren't the only zoo staff with a sharp eye for downed trees and limbs. Bringing in branches, logs, and downed trees, along with rocks and stumps, can make a habitat completely new for the occupants, providing new options for where to perch, sleep, eat, or hide behind/on top of. Strike a balance between finding what works and keeping comfortable object in place and freshening things up and promoting exploration by changing things around periodically.

- Experiment with pot(ted plants). There are a lot of zoo folks I know who take it for granted that live plants and live animals cannot mix. You put a plant in an enclosure, the animal will trample it, eat it, or otherwise kill it, they claim. To be sure, it can be hard to grow plants in an established animal exhibit, at least without barricading them off and blocking off access - and then there is all the fuss of watering, making sure they get through the winter, etc. An option is to put out large plants in pots for the animals to interact with. If the animals kill them, that's enrichment, as well as an incentive to find cheaper plants. If they survive, that's great - bring them inside for the winter and replace them outside in the spring

- Manage the elements. Make sure the animals in outdoor enclosures have access to sun and shade, fresh air and protection from the wind. Not only is it excellent for their health and welfare, but they will be able to exercise that much more control over their environment by making decisions about what conditions that want to experience - do they want to be out basking the sun, or dozing inside in the shade? Decisions, decisions.

None of these options if particularly expensive to implement, either in terms of time or money. You may be able to get some of these supplies donated. They make great volunteer projects for service groups. None of them will address some of the major issues you may have with an enclosure - it being too small, or not having enough indoor holding, or not being built in an ideal location within your zoo. They will, however, have the potential to make a marked difference in the quality of life for your animals.

There's a saying that I've heard periodically tossed around, "The Good is the Enemy of the Great." The meaning is, when things are "Okay" or "Good Enough," we settle for them instead of aspiring towards greatness. That may be, but there's another saying I like as well, "The Perfect is the Enemy of the Good." Here, the meaning is that we become so fixated on our ideal of perfection that we refrain from doing an imperfect, but still good, job.

I'll never stop wanting to make perfect - or at least, the best possible - habitats for the animals that I care for. Still, there's no reason not to try and improve them as much (and cheaply) as possible in the meantime.

Saturday, December 8, 2018

Sporcle Quiz: The Marvel-ous Zoo

Far more familiar to most members of the public than the wolverine is the X-Men character who is named for it. It's not alone. The late, great Stan Lee and his colleagues apparently took a lot of inspiration from the animal kingdom in coming up with their characters, and there is pratically a zoo's worth of heroes and villains to be found in the pages of Marvel comics. Can you name the characters named after animals?

Thursday, December 6, 2018

The Art of the "Wow" Factor

"You know, the first attraction I built when I came down from Scotland was a flea circus. Petticoat Lane. Really, quite wonderful. We had a wee trapeze, a merry-go... carousel. And a seesaw. They all moved, motorized of course, but people would say they could see the fleas, 'Oh mommy, I can see the fleas, can't you see the fleas?' Clown fleas, high-wire fleas, fleas on parade. But with this place, I wanted to give them something that wasn't an illusion. Something that was real. Something they could see, and touch."

- Jurassic Park

My lifelong dream of designing and building my own zoo - preferably with an unlimited budget, mind you - had a few root causes. First and foremost was my love of animals, my desire to be surrounded by them and to give them the best possible habitats under my care. I'm not ashamed, however, to admit that there was a puckish element to it also - a flair for showmanship. I saw designing a zoo as an artform in itself, a chance to create a magical experience like no other.

Two experiences bookend this later motive of mine, both of which took place at the National Zoo.

I still remember visiting the National Zoo as a child shortly after the famous O-Line - that marvelous series of towers and cables that snakes along the main path - opened, allowing orangutans to swing over the heads of guests. I didn't realize how lucky I was to see the apes above me on that first visit - in subsequent trips to DC, I only rarely see them climbing it. What I did realize, however, even at that young age, was what a unique, special experience it was. Never mind that I had never seen an orangutan in the flesh before at all - I knew that what I was seeing was different than I would see when visiting an orangutan at any other zoo. Someone had really thought outside of the box when planning this, I realized later, and I wondered how much doubt and derision they must have overcome to turn this into a reality.

Decades later, I was visiting the National Zoo again, this time in the company of a friend from South America on his first trip to the United States. Amid the elephants and lions and, of course, pandas, I almost neglected to take him to Amazonia. What could a zoo rainforest building offer to a man who had hiked through the real Amazon on several occasions, I thought? Well, we went in anyway - and he was transfixed. Not by the parrots or monkeys, but by the fish. His country had several zoos, but no public aquariums, and the rivers he had explored were far too dark and turbid to see into. He parked himself in front of the massive aquarium of arapaima, pacu, and other giant river fish, and he was spellbound. He had walked alongside rivers that naturally held these species. He had seen them hooked or netted and hauled onto land, destined for the meat markets. But he had never thought of what it would be like to see them, alive and eye-to-eye, as they swam by him, inches away.

I'm a lot older than I was when I first watched an orangutan climb overhead, but on lucky occasions, I still find a zoo experience that leaves me spellbound. There is a facility in Alberta, Canada (the unoriginally-named polar bear habitat) where you can swim - in pools separated by some extremely strong glass - alongside polar bears. At the San Antonio Zoo, on special occasions you can try your strength in a tug-of-war with a lion (spoiler alert - you will lose). At Disney's Animal Kingdom Lodge, you can wake up in the morning and saunter out of your hotel room to be greeted by herds of African ungulates. At plenty of zoos, there is a chance to have some interaction with animals, whether it's a kangaroo walk-through, a lorikeet feeding aviary, or a giraffe-feeding station.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2011/07/14/got_a_spare_bear_town_of_cochrane_tourist_attraction_needs_help/cochrane_polar_bearhabitat.jpeg)

Polar Bear Habitat, Toronto Star

I think a lot about the dreamer who first imagined an experience where orangutans travel overhead, swinging carelessly above dazzled visitors. It was a risky idea, but it has worked marvelously. I wonder what brilliant, crazy ideas are locked in the heads of zookeepers, aquarists, and curators as I type this, just waiting for the chance to be given life. I wonder when next I'll be spellbound. I wonder if I'll ever have the idea - and the means to create it - that will captivate a crowd of my own.

- Jurassic Park

My lifelong dream of designing and building my own zoo - preferably with an unlimited budget, mind you - had a few root causes. First and foremost was my love of animals, my desire to be surrounded by them and to give them the best possible habitats under my care. I'm not ashamed, however, to admit that there was a puckish element to it also - a flair for showmanship. I saw designing a zoo as an artform in itself, a chance to create a magical experience like no other.

Two experiences bookend this later motive of mine, both of which took place at the National Zoo.

I still remember visiting the National Zoo as a child shortly after the famous O-Line - that marvelous series of towers and cables that snakes along the main path - opened, allowing orangutans to swing over the heads of guests. I didn't realize how lucky I was to see the apes above me on that first visit - in subsequent trips to DC, I only rarely see them climbing it. What I did realize, however, even at that young age, was what a unique, special experience it was. Never mind that I had never seen an orangutan in the flesh before at all - I knew that what I was seeing was different than I would see when visiting an orangutan at any other zoo. Someone had really thought outside of the box when planning this, I realized later, and I wondered how much doubt and derision they must have overcome to turn this into a reality.

Decades later, I was visiting the National Zoo again, this time in the company of a friend from South America on his first trip to the United States. Amid the elephants and lions and, of course, pandas, I almost neglected to take him to Amazonia. What could a zoo rainforest building offer to a man who had hiked through the real Amazon on several occasions, I thought? Well, we went in anyway - and he was transfixed. Not by the parrots or monkeys, but by the fish. His country had several zoos, but no public aquariums, and the rivers he had explored were far too dark and turbid to see into. He parked himself in front of the massive aquarium of arapaima, pacu, and other giant river fish, and he was spellbound. He had walked alongside rivers that naturally held these species. He had seen them hooked or netted and hauled onto land, destined for the meat markets. But he had never thought of what it would be like to see them, alive and eye-to-eye, as they swam by him, inches away.

I'm a lot older than I was when I first watched an orangutan climb overhead, but on lucky occasions, I still find a zoo experience that leaves me spellbound. There is a facility in Alberta, Canada (the unoriginally-named polar bear habitat) where you can swim - in pools separated by some extremely strong glass - alongside polar bears. At the San Antonio Zoo, on special occasions you can try your strength in a tug-of-war with a lion (spoiler alert - you will lose). At Disney's Animal Kingdom Lodge, you can wake up in the morning and saunter out of your hotel room to be greeted by herds of African ungulates. At plenty of zoos, there is a chance to have some interaction with animals, whether it's a kangaroo walk-through, a lorikeet feeding aviary, or a giraffe-feeding station.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2011/07/14/got_a_spare_bear_town_of_cochrane_tourist_attraction_needs_help/cochrane_polar_bearhabitat.jpeg)

Polar Bear Habitat, Toronto Star

I think a lot about the dreamer who first imagined an experience where orangutans travel overhead, swinging carelessly above dazzled visitors. It was a risky idea, but it has worked marvelously. I wonder what brilliant, crazy ideas are locked in the heads of zookeepers, aquarists, and curators as I type this, just waiting for the chance to be given life. I wonder when next I'll be spellbound. I wonder if I'll ever have the idea - and the means to create it - that will captivate a crowd of my own.

Wednesday, December 5, 2018

Building Your Dream Zoo

"It's a pretty good zoo said young Gerald McDrew,

And the fellow who runs it seems proud of it too

But if I ran the zoo, said young Gerald McDrew,

I'd make a few changes, that's what I'd do."

- If I Ran the Zoo, by Dr. Seuss

When I was young, one of my favorite pastimes was to design my zoo - on long car rides I'd mentally lay out the paths and the exhibits, stocking them with a laundry-list of my favorite animals. Whenever the combination of a pen, a piece of paper, and an idle moment came together, I'd doodle out maps. These weren't simple sketches, either - I'd plan it down to the size of the enclosures and the individual numbers of each species.

Sometimes these schemes were inspired by the particulars of a specific zoo I had visited (not many of them, though - despite my lifelong passion for them, before I went away to college I had only ever visited a small number of zoos), or something I had read about (the internet not really being much of a resource back then). Other times, I made them up whole out of cloth. Those were probably my favorite ones. I didn't have to try to shoehorn an idea or a vision I had into an existing landscape. I was able to let my imagination go wild. Instead, I got to plan everything out so it all fit together, smoothly and seamlessly. I tried to create things that had never been done before. When I walked through the zoos of my imagination, I wasn't just going for a walk among the animals. I was telling myself a story, or going on an adventure.

This came to a head in high school, when a gullible if well-meaning teacher agreed to let me indulge my interest in zoo design for a final project. I buried the poor man alive under fifty pages - double-sided, single-spaced - of text, drawings, and diagrams.

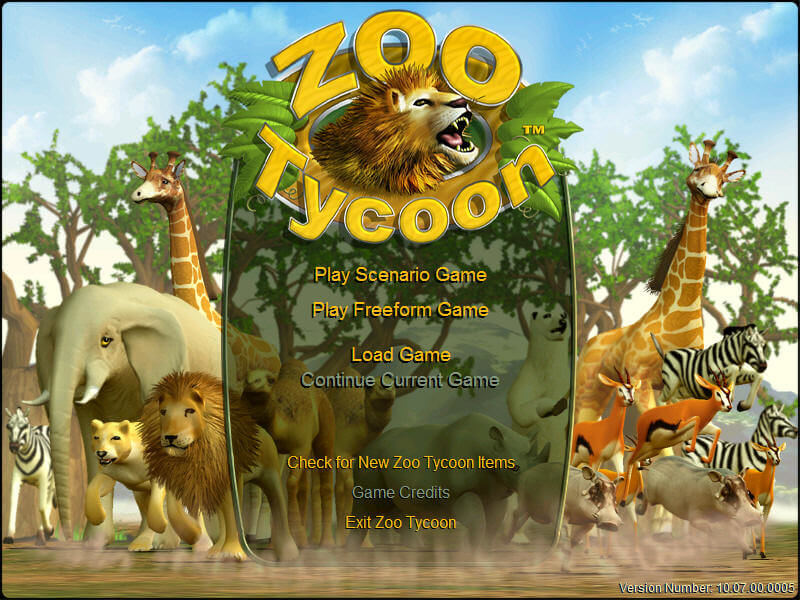

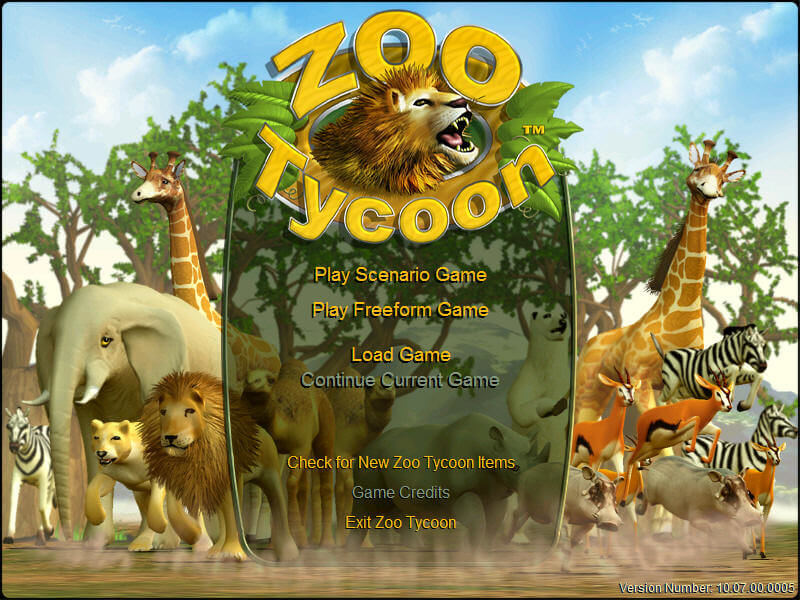

To this day, my favorite part of the job is the planning and designing of new exhibits - working on the layout, selecting the animals, and putting shovels in the ground to make them a reality. This doesn't get to happen nearly as often as I would like it to. Unlike my childhood ramblings - or even Zoo Tycoon - building a new zoo exhibit is very expensive in terms of labor and money, and not something done lightly on a whim.

Still, on those days when the projects are in motion and a new piece of the zoo is being built, and I know that I'm one of the minds that made it happen, I'm probably the happiest person I know.

Tuesday, December 4, 2018

Species Fact Profile: Wolverine (Gulo gulo)

Wolverine

Gulo gulo (Linnaeus, 1758)

Range: Canada, Northern United States, Scandinavia, Russia

Habitat: Boreal Forest, Tundra

Diet: Small Mammals, Ungulates, Birds, Eggs, Carrion, Roots, Berries, Seeds

Social Grouping: Solitary, Territorial (male territories encompass several females)

Reproduction: Mating takes place in late spring and summer. Implantation of embryo is delayed for up to 6 months after breeding, after which pregnancy is 30-50 days. Average of 3 kits born in den dug in the snow. Weaned at 3 months, independent at 5-7 months, and sexually mature at 2-3 years old

Lifespan: 10-15 Years

Conservation Status: IUCN Least Concern

- Largest member of the Mustelidae (weasel family). Body length 65-105 centimeters, tail length 13-26 centimeters, shoulder height 36-45 centimeters. Weigh 9-30 kilograms. Females are usually about two-thirds the size of the males

- Body is short and stocky with short legs, a large head with small ears, and semi-retractable claws. The paws are broad and hairy to assist in traveling across thick snow

- Fur is brown or black with a yellowish stripe extending from the crown across each shoulder and meeting up again on the tail

- Excellent sense of smell and good sense of hearing, but relatively poor vision

- Have a reputation for ferocity, famous for challenging larger carnivores, such as pumas and wolves, for access to a carcass. Adults have few natural predators, except for occasionally wolves. Youngsters may be preyed upon by pumas, bears, or eagles

- Range is believed to be limited by snow, requiring enough snow late into the spring that prey can be cached and kept fresh until the kits are old enough to forage on their own

- Does not hibernate. Primarily active by night, but will also forage by day

- Capable of killing large ungulates such as caribou that are stranded in deep snow. Large kills will be befouled with musk and urine to dissuade other animals from eating them

- Sometimes hunted for the fur, which is frost resistant, but little trade in their pelts. It is possible that Michigan's nickname as "the Wolverine State" is due to Detroit's historical importance in the fur trade; it is unknown as to whether the species was found historically in Michigan

- Persecuted historically for predation of trapped fur-bearing animals and domestic reindeer, as well as the animals' tendency to break into trappers cabins and befoul them with musk. Very difficult to trap, reported to spring and destroy or bury traps set for them

- Prominently featured in folklore and myth, often as a trickster or devil spirit, sometimes as a creator

- Two subspecies - the North American (G. g. luscus) and the Eurasian (G. g. gulo). Both look very similar, differences are mostly genetic. Vancouver Island population shows some differences in skull morphology, may represent a third subspecies, G. g. vancouverensis

- Populations in decline, in part due to loss of large carnivores that they can scavenge off of. Very sensitive to human disturbance, breed slowly

Zookeeper's Journal: Most people only know the wolverine as an X-Men character, and its no surprise. The world's largest weasel is seldom seen in zoos, where it has proven challenging to breed. I've only seen wolverines at three facilities, and only one of those was outside of the species natural range. For such notoriously tough animals, wolverines are rather delicate and sensitive in their climatic preferences, and easily become too hot or uncomfortable. Unfortunately, the future in the wild may be too hot for them to handle; while polar bears are the poster species for global climate change, wolverines may prove to be even more vulnerable as they lose the snow dens where they raise their young become a thing of the past.

Sunday, December 2, 2018

Do You Tycoon?

As an adult, I find the Christmas holidays exhausting. I'm cold and cranky. I still have to work. There's the added stress of holiday events at the zoo. Most of my bill-chickens decide to come home to roost in early December, hitting the ol' bank account. It seems like every year there are more people who snake their way onto the list of people I need to get gifts for. This is offset by the fact that, as I am nagged annually by my folks about what I want for Christmas, my answer usually ends up being... nothing, really.

I mean, there are things I need every year, like new work pants and small household objects and the junk food that fuels my will to live, but those are usually "I need now" kinds of purchases of the sort that can't wait until late December.

Oh, for the glorious, greed-fueled Christmases of yore, when the holidays were sparked with the joy of all the wonderful things I just knew I needed to be happy. While visiting my family this Thanksgiving, I wondered up to my old bedroom and there, on a the shelf, was a blast from the past, my must-have Christmas gift from almost two decades ago. It was a copy of the only computer game I'd ever owned - Zoo Tycoon.

For those not privileged enough to have enjoyed the game, Zoo Tycoon is essentially the SIMS for zoos. You purchase animals, build enclosures for them to their liking, and hopefully get them to be fruitful and multiple. You add attractions to lure in guests, beautify your grounds, and hopefully watch the money roll in, fueling your ability to get more animals and keep the cycle going. Initially featuring forty species to choose from, including most of the zoo staples - elephants, rhinos, hippos, lions, tigers, polar bears, and gorillas, among them - a series of expansion packs and downloads brought the total up to over one hundred, including Marine Mania, with sharks, orcas, and other sea beasts, and Dinosaur Digs, where you can clone your way into making a Jurassic Park-style attraction with dinosaurs and other prehistoric beasties. Zoo Tycoon has been replicated twice with newer, fancier features (including a visitor mode, where you can walk through your zoo and see the exhibits from the perspective of a guest, but I still have a special fondness for the original 2001 game.

As a kid I loved anything zoo-related, so this game was a natural draw for me. The last time I played it, I was just starting off in the field. I remember being somewhat jaded at how it took me only one click of the mouse to install a section of chainlink fencing in the game, while I had spent several hot, sweaty hours doing the real thing just hours earlier. Also, I had the option of erasing a section of fencing and letting jaguars and hyenas chase down obnoxious zoo visitors who complained to much in the game without any real consequences, something that I suspect would have been frowned upon in real life.

My mother is always badgering me about when I'm finally going to settle down and get a permanent house somewhere so I can come home, collect all of my childhood belongings, and give her another empty room to tinker around with (which, I suspect, is her real life version of Zoo Tycoon). This Thanksgiving, I made it a little easier and took a small batch of possessions back to my apartment with me. Among them was my copy of Zoo Tycoon. This Christmas, after I come home from work, I'm going to make myself a special dinner as only a bachelor living in a small apartment far away from home can, I'm going to get into my warm pajamas, and then I'm going to play some Zoo Tycoon for the first time in years. In doing so, I'm going to remember what it was like when I got one of my favorite (non-living) Christmas gifts and got to first play with my longest-held dream of building my own zoo... even if the image was a little small and a little grainy.

Saturday, December 1, 2018

The Season for Compassion

Yesterday wasn't a great day for the zoo community. First, from Britain came the tragic news that a snow leopard escaped from its enclosure at the Dudley Zoo, presumably due to keeper error, and was fatally shot as safety protocols dictated in the situation. Then, from Oregon Zoo, came the sad loss of their youngest elephant to the dreaded Elephant Endotheliotropic Herpesvirus, a devastating killer of elephants both in zoos and in the wild. At both facilities, staff and friends are heartbroken... and the collective community of internet trolls is sharpening knives.

Last night, everyone was an animal expert.

It isn't just animal issues, of course. Whenever anything goes wrong on any front... anywhere, the internet is lit up with people who claim to know what to do better and how everyone involved is stupid and quite possibly evil. Ironically for someone who has a blog, I don't actually post much myself on social media, but I do spend a decent amount of time on it, so I see the chaos at work. Once or twice, my zoo - and so, as I interpreted it at the moment, me, personally - where in cross hairs.

Some of the folks posting vitriol are just trolls, and you should never, ever, feed the trolls. A lot of them, however, are mostly well-meaning people who get carried away over the relatively anonymous internet. (And a small but annoying percentage are other zookeepers, because let's be honest, sometimes we can be a little catty with one another). A large part of it, I suspect, is that they don't want to accept that bad things happen, either due to a momentary lapse in judgment or concentration or due to just bad luck. By blaming someone else and coming down with two feet, they are really trying to reassure themselves that such a thing would never, ever happen to them.

I would ask that we all take a step back and try not to be that person.

Yes, at Dudley Zoo a mistake was made that had terrible consequences, and that will be dealt with appropriately... by Dudley Zoo. Not by you, stranger from Iowa who has never even been to the UK. Yes, the Oregon Zoo is aware of EEHV in the same way that human doctors are aware of cancer - it's a terrible disease, there is a lot of research going into a cure, but that doesn't mean that no one is trying or that every loss can be prevented.

This holiday season, and continuing beyond it, maybe we can try to be a little more compassionate in our dealings with each other. The time will come when all of us will be in a sad situation, maybe of our own doing, maybe not, and when that time comes, all of us will want a shoulder to lean on - not yet another punch to the gut.

Thursday, November 29, 2018

Just Browsing

I'm not a great joke teller. I try, but then I usually get embarrassed midway through at the cheesiness of the joke and rush my way through. Also, I sometimes try for something too esoteric and it misses the mark with my crowd. Take this one, for instance...

A giraffe walks into a bookstore. It spends several minutes poking its face into the topmost shelves before a clerk finally walks up and asks, "Need help finding anything?" "No, thanks," the giraffe replies. "I'm just browsing."

It's a zookeeper pun - "browsing" is the act of foraging for leaves, as opposed to "grazing," the act of eating grass. Giraffes and okapis are browsers. Moose are browsers. Sumatran rhinoceroses are browsers. Zebras and wildebeest and bison are grazers.

In the wild, browsing mammals spend a whole lot of time, well, browsing, so it's not surprising that in a zoo setting, we would want to replicate that behavior. The problem is that herbivores have huge appetites, and even in a relatively large enclosure, it won't take too long for most plant-eaters to gobble up every scrap of edible greens. The task then falls to us, the keepers, to find fresh foliage and harvest it for the animals. These leafy treats are called "browse" by the animal care staff.

For some keepers, the hunt for browse is one of the most time-consuming chores of the week, with eyes always peeled for freshly downed branches, especially after a storm or when tree trimming is being done (the larger branches are also sought after eagerly by bird and primate keepers, who wish to use them for perching).