Not too long ago, a zoo that I worked at wanted to revamp its native species exhibits. Among the exhibits to be refurbished was a habitat for American toads, a common, almost omnipresent species in our part of the country.

Now, there is no Species Survival Plan for American toads. As small as they are, there isn't a ready supply of non-releasable injured toads that can be adopted out from rescue centers either (as any toad that is injured in the wild would likely be killed outright or eaten shortly after). Instead, one of the keepers was dispatched with a plastic bucket and directed to take a walk through the zoo. A few minutes later, she was back with four toads.

At this time, the

Association of Zoos and Aquariums manages over five hundred species survival plans, covering animals as divergent as

beluga whales and

red-kneed tarantulas. Most species are selected for inclusion in an SSP because of their conservation status, taxonomy uniqueness, or exhibition value, often some combination thereof. Many new zoo exhibits are essentially planned

around these animals, as these are the species that are available to work with.

Many zoos also have native exhibits, however. Some facilities, such as the

Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum and the

Virginia Living Museum, are entirely native-focused. These facilities want to display a comprehensive sampling of the species found in their region. Some native US species are part of breeding programs, especially highly endangered ones, such as

whooping cranes and

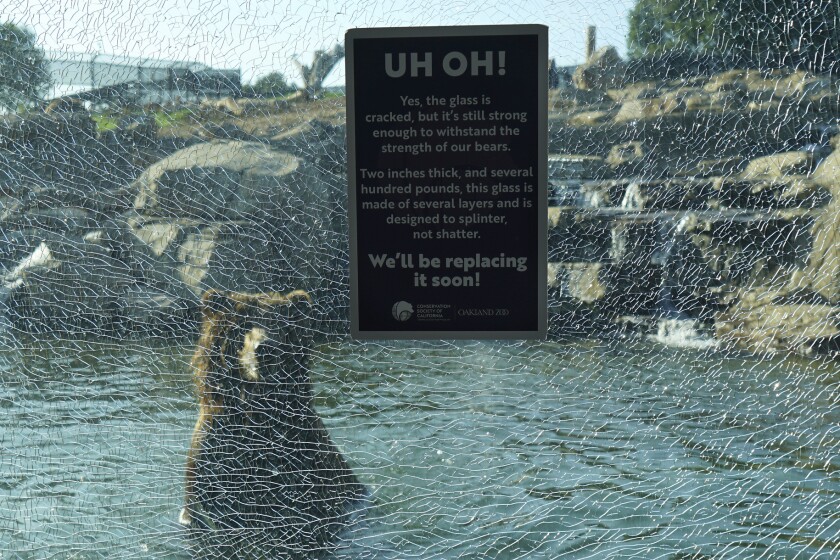

bog turtles. Most are not. In some cases, especially with birds and mammals, zoos can obtain specimens by taking in animals that are deemed non-releasable or nuisances (this is where virtually all bald eagles, American black bears, pumas, and white-tailed deer in American zoos come from). Others, especially in the case of reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, may be taken from the wild.

If a species is not federally protected, then the ability of a zoo, aquarium, museum, university, or private individual for that matter, to take specimens from the wild is left to the state. Some states require special permits to collect wild animals and require detailed reporting. Others allow almost anything to go, if the species in question is not legally protected on the state or federal level. With very common native species, such as American toads, there is likely to be little issue with collecting.

Legal and ethical aren't used interchangeably, however, which does beg the question - if zoos no longer deem it appropriate to take large mammals from the wild in all but the most important of cases (such as a rescue, or getting important new genetic material for a population), is it okay for them to take a toad, or a tarantula, or a turtle? It's a question I hadn't really thought of very much before. When we ponder the concept of animal freedom, we're more likely to be thinking about big cats, bears, and elephants rather than toads. We generally assume that if the toad is well fed, safe, and in a comfortably provisioned habitat, it's probably fine. After all, we're talking about animals that in their natural state might not move more than a few feet a day, not migrating over vast distances.

I think that as long as these animals are being well-cared for and their husbandry and welfare is being monitored closely, it's very beneficial to have them in an exhibit setting so that people can learn about them and appreciate them. The requirements must be met, the zoo must be able to demonstrate that animals are living their natural lifespan or beyond, and indications of stress/discomfort must be minimal. That is to say, an aquarium shouldn't be allowed to pull great white shark after great white shark from the ocean for an exhibit, replacing each right after it dies at a young age. All collection from the wild must be well documented and follow to the letter all local laws, including permits.

For many of these species, I do not think it beneficial to start formalized breeding programs, as they would compete with other, more conservation-dependent species in terms of time and resources (a hypothetical American toad breeding program would take away space from a Puerto Rican crested toad breeding program, for instance).

I've collected a decent number of native herps and invertebrates for exhibits before. Some have been permanent members of the collection. Some have been kept for short periods of time and then released. I've done so legally in all cases (which on one occasion included playing dumb when a tyrannical boss told me to bring him some bog turtles on my next expedition, which I was 100% not willing to do).

I've learned a lot from each, and like to think that they've helped teach the public a great deal about the natural world we live in.