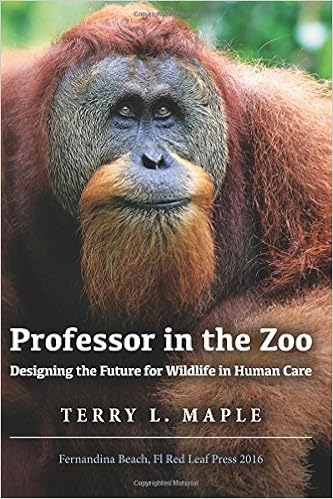

Much of that success can be laid at the feet of Dr. Maple, now serving as Professor in Residence at the Jacksonville Zoo. Dr. Maple outlines the experiences which led to the rebirth of Zoo Atlanta, as well as his vision for expanding on that success at zoos around the country, in Professor in the Zoo: Designing the Future for Wildlife in Human Care.

The book goes back and forth between two intersecting trains of thought. There is the reflective phase, where Dr. Maple recounts how he came to be behind the director's desk in Atlanta and how he worked to turn the zoo around when its doom seemed imminent. That's an enjoyable, feel-good read, especially as we explore the tactics that the staff used to improve animal care and the visitor experience, some of which I'm keen to try out in my own zoo. Secondly, there is the visionary phase, where Dr. Maple describes his dreams of changes that could be made to improve animal care across the country. Some of these are straightforward ideas that most zoos are trying to implement - bigger enclosures, more natural social groups, more enrichment. Some are a little more controversial, such as more collaboration with organizations such as Humane Society of the United States and maybe even *gulp* PETA. An entire chapter is devoted to SeaWorld and how it can survive and even thrive in a post-Blackfish environment.

If Dr. Maple has one major idea he wants to push, it's the desire for more empirical, scientific-based management of zoo animals. It's pretty much spelled out in his new job title at Jacksonville, to say nothing of the title of the book. I can see where he's coming from. From my experience, a lot of what goes into zoo management of animals is based on intuition, superstition, and a certain degree of "Well that's how we've always done it." I've heard lots of zoo professionals, newbie and veteran alike, who are adamant that what they do works, but who can't really back it up with any proof, other than the animal is still alive at that given moment. I've heard plenty of cases where several employees are adamant that they are correct, even when they are saying the exact opposite thing. Taking a more scientific approach to animal management, with measured results and controlled variables, can help us formalize our animal care and make sure that what we are doing really is providing the best possible results. It can also help us build on successes and improve upon them. Similarly, having more cold, hard, empirical data can be useful when confronting those who are opposed to our missions, be they activists or government bureaucrats.

It will, however, require an expenditure of effort, time, and resources, which is probably why we aren't doing it as much as we should be.

My own boss, the director at my zoo, has always disliked the title of "Curator." To him, a curator is someone at a museum or an art gallery, someone with an advanced degree who sits behind a desk with rows of musty books behind him. In his eye, that's not what a zoo needs. Terry Maple disagrees, and I'm starting to fall into his camp. Yes, we need people with animal sense, who aren't afraid to get dirty, work hard, and sometimes rely a little on intuition and gut. At the same time, we should embrace the science-side of our profession with just as much vigor. "Zoo," after all, is short for "zoological park," referring to the scientific study of animals. The very first public zoos were gardens to science, and there's something to be said for getting back to one's roots.

All of us in the profession became zookeepers and aquarists because we care about animals and want to do our best for them. Dr. Maple, based on decades of experience in the field, triumphing over some very adverse conditions, has shown us a new series of tools that we can use to work towards that goal. We can't afford to ignore them.

No comments:

Post a Comment