Well, I'm glad the folks at the Houston Zoo found a good use for one, at least. That llama looks a lot happier to see a leaf-blower than I ever was.

Search This Blog

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

Llama Blowout at the Houston Zoo

Leaf-blowers are my least favorite tool to use in the entire zoo. This probably dates back to my earliest years as a keeper, where I was assigned the horrendously crappy job of blowing an entire barn's worth of goat and sheep pellets (euphemism for poop) and uneaten grain into one pile, and would get reamed out if I missed a single raisin-sized drop. Leaf-blowers are great for scattering things to the four winds... less so at gathering them into one pile.

Well, I'm glad the folks at the Houston Zoo found a good use for one, at least. That llama looks a lot happier to see a leaf-blower than I ever was.

Well, I'm glad the folks at the Houston Zoo found a good use for one, at least. That llama looks a lot happier to see a leaf-blower than I ever was.

Monday, June 27, 2016

Editorial: Lions and Tigers Don’t Belong in Zoos. But Some Animals Do.

This editorial (posted on Slate, by Matt Soniak) was interesting enough in that it actually tried to do something that very few people do in zoo controversies - find sensible middle ground. It recognizes that yes, there are essential reasons for keeping zoos and aquariums around, and yes, some species do depend on them for their very survival. I found some of the ideas in it a bit quixotic, however, and talking about "freeing" gorillas and tigers just strikes me as idiotic (no one seriously suggests "freeing" such animals, they talk of phasing them out through managed cessation of breeding).

Mostly, I enjoyed the comments, however, which is something I rarely do in online articles. Instead of the typical "I saw a tiger and it made me sad" rubbish, people were actually weighing options for helping sustain the conservation efforts of smaller, more endangered species. And all seem to have come to the same conclusion/

One reader put it best - "Could resources be better apportioned? Sure. But any plan whose real goal is making zoos go bankrupt because no one is going to pay to see a Sierra Nevada frog, is not only counter productive - it's dishonest and deceitful."

After a 4-year-old child accidentally fell into a gorilla enclosure at the Cincinnati Zoo and forced the staff to euthanize an adult gorilla for the child’s protection in May, animal lovers rallied on behalf of Harambe, the gorilla, and against the practice of zoos in general. If the black-footed ferret had a Twitter account and a say in all this, I’m pretty sure it might have a different take. It is thanks to zoos’ efforts that the ferret survived at all. This success story offers a different alternative for what zoos could become. Rather than housing exotic animals that require habitat that far exceed what a zoo can reasonably offer, zoos should be converted into conservation centers equipped to help local struggling species find their footing again.

Mostly, I enjoyed the comments, however, which is something I rarely do in online articles. Instead of the typical "I saw a tiger and it made me sad" rubbish, people were actually weighing options for helping sustain the conservation efforts of smaller, more endangered species. And all seem to have come to the same conclusion/

One reader put it best - "Could resources be better apportioned? Sure. But any plan whose real goal is making zoos go bankrupt because no one is going to pay to see a Sierra Nevada frog, is not only counter productive - it's dishonest and deceitful."

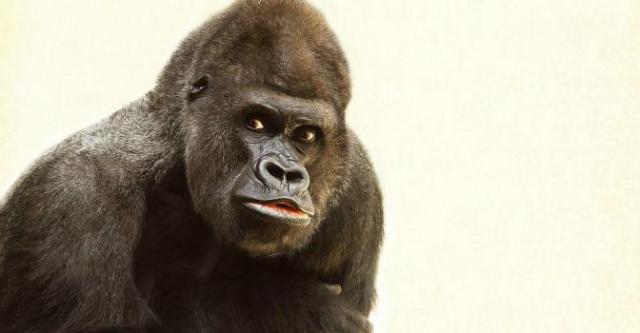

Shinda, a Western lowland gorilla, holds her newborn as they rest at the Prague Zoo in April - Michal Cizek/AFP/Getty Images

After a 4-year-old child accidentally fell into a gorilla enclosure at the Cincinnati Zoo and forced the staff to euthanize an adult gorilla for the child’s protection in May, animal lovers rallied on behalf of Harambe, the gorilla, and against the practice of zoos in general. If the black-footed ferret had a Twitter account and a say in all this, I’m pretty sure it might have a different take. It is thanks to zoos’ efforts that the ferret survived at all. This success story offers a different alternative for what zoos could become. Rather than housing exotic animals that require habitat that far exceed what a zoo can reasonably offer, zoos should be converted into conservation centers equipped to help local struggling species find their footing again.

Sunday, June 26, 2016

Sporcle Quiz: Animals in Other Words

Or I could just let the Marx Brothers make all of the animal puns...

Saturday, June 25, 2016

Washed Ashore - An Exhibit at the National Zoo

Sharks, swordfish, and other sea creatures recently debuted at the National Zoological Park - but not real ones. Instead, the public was introduced to greater-than-life-sized sculptures of some of the ocean's most iconic animals - made of trash. More specifically, they were made of trash from the ocean that has been carried back to the beaches by the tide.

Washed Ashore: Art to Save the Sea is on display at the National Zoo through September 5th. As the summer heats up, more and more zoo and aquarium visitors will also be spending time on the beach. It's important to remember that trash packed onto the beach also needs to be packed out, before it finds its way into the ocean, where it can harm marine life.

Washed Ashore: Art to Save the Sea is on display at the National Zoo through September 5th. As the summer heats up, more and more zoo and aquarium visitors will also be spending time on the beach. It's important to remember that trash packed onto the beach also needs to be packed out, before it finds its way into the ocean, where it can harm marine life.

Tuesday, June 21, 2016

Leave Dory Alone

The start of the summer usually marks the end of the zoo-and-aquarium visiting season for me. Part of it is that I'm so busy at my own facility that I can't get away for very long. Part of it is also that all of the other zoos and aquariums are usually so crowded that I'd rather wait until the fall. Still, this last week I paid one last aquarium visit before the long slog of summer sets in and, despite the crowds, it was enjoyable enough.

Out of habit, both when working at my zoo and when visiting others, I tend to keep an ear half-cocked at all times to hear what visitors are saying. Are they talking about the animals? Are they learning anything? Are they enjoying their visit? What do they like? What didn't they? What are they talking about?

On this trip, the answer was easy. Dory. Everybody was talking about Dory, and every bluish fish was "Dory." When visitors actually found the blue tangs themselves, the crowds, as they were, went wild.

This happens all of the time when an animal is portrayed in movies, especially movies geared towards kids. Meerkats and warthogs rocketed to stardom following Disney's The Lion King. For awhile, every sloth was "Sid", from Ice Age, only to eventually fade into the sloths from Zootopia. And, of course, when Finding Dory's prequel, Finding Nemo, came out, everyone was all about clownfish. Now that Marlin's memory-challenged side-kick Dory has a movie of her own, tangs are all the rage.

The difference between The Lion King and Finding Nemo, of course, is that relatively few moviegoers will then rush out and buy a meerkat. Clownfish and tangs, however, are another story.

There's plenty of precedent. When I was a kid, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were the coolest thing ever (this being before Michael Bay came along and ruined yet another childhood memory for me). Lots of kids went out and got pet turtles. Then, perhaps becoming frustrated because said turtles did not talk, do karate, or thrive on shared pieces of pizza, the kids ignored their shelled charges, many of which died in squalid conditions. The same has happened with clownfish and tangs.

I have nothing against people owning clownfish... or tangs... or turtles (meerkats I may draw a line at). What I am against is people making impulse buys that will support an unsustainable aquarium trade in wild-caught fish which will then die due to inadequate care. I'm an exotic pet owner myself, and as much as zookeepers like to complain about them, the truth is that many of us are. But I researched my pets carefully, got them from someone I know and trust, and invest in their care. Which is important to me... because I also have several enclosures' worth of former exotic pets with owners who failed to care for them correctly.

So if you enjoy Finding Dory a lot, as many people seem to, and decide that you want to get a pet fish, good for you. It may open a new hobby to you that leads to a lifetime of enjoyment. But make sure that this is something that you will stick with, for the sake of the animals who will be in your care. Start small, with species with simpler care requirements - certainly freshwater fish over saltwater, for beginners. Get them from a reputable, sustainable source. Be willing to provide appropriate housing, diet, and care.

If you can't keep it properly, don't keep it at all. I'm sure Dory and her friends would be just as happy to be left alone.

Out of habit, both when working at my zoo and when visiting others, I tend to keep an ear half-cocked at all times to hear what visitors are saying. Are they talking about the animals? Are they learning anything? Are they enjoying their visit? What do they like? What didn't they? What are they talking about?

On this trip, the answer was easy. Dory. Everybody was talking about Dory, and every bluish fish was "Dory." When visitors actually found the blue tangs themselves, the crowds, as they were, went wild.

This happens all of the time when an animal is portrayed in movies, especially movies geared towards kids. Meerkats and warthogs rocketed to stardom following Disney's The Lion King. For awhile, every sloth was "Sid", from Ice Age, only to eventually fade into the sloths from Zootopia. And, of course, when Finding Dory's prequel, Finding Nemo, came out, everyone was all about clownfish. Now that Marlin's memory-challenged side-kick Dory has a movie of her own, tangs are all the rage.

The difference between The Lion King and Finding Nemo, of course, is that relatively few moviegoers will then rush out and buy a meerkat. Clownfish and tangs, however, are another story.

There's plenty of precedent. When I was a kid, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were the coolest thing ever (this being before Michael Bay came along and ruined yet another childhood memory for me). Lots of kids went out and got pet turtles. Then, perhaps becoming frustrated because said turtles did not talk, do karate, or thrive on shared pieces of pizza, the kids ignored their shelled charges, many of which died in squalid conditions. The same has happened with clownfish and tangs.

I have nothing against people owning clownfish... or tangs... or turtles (meerkats I may draw a line at). What I am against is people making impulse buys that will support an unsustainable aquarium trade in wild-caught fish which will then die due to inadequate care. I'm an exotic pet owner myself, and as much as zookeepers like to complain about them, the truth is that many of us are. But I researched my pets carefully, got them from someone I know and trust, and invest in their care. Which is important to me... because I also have several enclosures' worth of former exotic pets with owners who failed to care for them correctly.

So if you enjoy Finding Dory a lot, as many people seem to, and decide that you want to get a pet fish, good for you. It may open a new hobby to you that leads to a lifetime of enjoyment. But make sure that this is something that you will stick with, for the sake of the animals who will be in your care. Start small, with species with simpler care requirements - certainly freshwater fish over saltwater, for beginners. Get them from a reputable, sustainable source. Be willing to provide appropriate housing, diet, and care.

If you can't keep it properly, don't keep it at all. I'm sure Dory and her friends would be just as happy to be left alone.

Monday, June 20, 2016

Species Fact Profile: Pancake Tortoise (Malacochersus tornieri)

Pancake Tortoise

Malacochersus tornieri (Siebenrock, 1903)

Range: East Africa (Southern Kenya, Northern Tanzania)

Habitat: Rock Kopjes (Isolated Rock Outcrops)

Diet: Vegetables, Fruit, Carrion, Invertebrates

Social Grouping: Sociable (Will share burrows)

Reproduction: Female lays single large egg per nesting, spaced 25 days apart. May lay as many as 6 eggs per year. Eggs buried in soil or sand, incubate for 180-240 days. Sexual maturity based on body size (usually at about 8 years old)

Lifespan: 25 Years

Conservation Status: IUCN Vulnerable, CITES Appendix II

- Body length up to 18 centimeters, but very flat - no more than 6 centimeters thick at thickest - leading to common name. Weight about 500 grams. Males are slightly smaller than females

- Carapace is brown or beige with varying patterns of radiating, dark lines

- Soft, flat shell is an adaptation for squeezing into rock crevices to avoid predators; it is so unusual among tortoises that the first scientists to observe these tortoises thought they were suffering from some sort of bone disease. Flat shell also allows for rapid heat absorption

- Flat shell also makes body cavity very small, meaning these tortoises can only lay one egg at a time.

- World's fastest tortoise species, clocked at 18 meters per minute, also skilled climber. The flat shell allows the tortoise to right itself quickly if it flips over

- Declining due to habitat destruction and over-collection for the pet-trade; recovery is hampered by their slow reproductive rate

Friday, June 17, 2016

The Central Park Zoo Escape of 1874

"All citizens, except members of the National Guard, are enjoined to keep within their houses or residences until the wild animals now at large are captured or killed. Notice of the release from this order will be spread by the firing of cannon in City Hall Park, Tompkins square, Madison square, The Round and at Macomb's Dam Bridge. Obedience to this order will secure a speedy end to the state of siege occasioned by the calamity of this evening."

Perhaps one of the most extraordinary antecdotes of the Central Park Zoo's history is the one that never actually happened. I should probably explain that a bit. On November 9th, 1874, the New York Herald posted a sensational story describing how the animals of the zoo escaped en masse and wreaked havoc in New York. A rhinoceros gored a keeper to death. Tigers chased after society ladies. Tapirs, anacondas, and hyenas ran amok. It was the most horrifying spectacled the city ever saw until the September 11th attacks over 120 years later.

Only at the end of the article did the paper finally own up to the fact that “Of course, the entire story given above is a pure fabrication. Not one word of it is true.” It was written by the paper after one of its editors witnessed the near-escape of a leopard at the zoo, and was meant to be a critique of the zoo's safety practices. Still, how many people read to the end of a long newspaper article? The Herald was criticized for inciting panic.

All citizens, except members of the National Guard, are enjoined to keep within their houses or residences until the wild animals now at large are captured or killed. Notice of the release from this order will be spread by the firing of cannon in City Hall Park, Tompkins square, Madison square, The Round and at Macomb's Dam Bridge. Obedience to this order will secure a speedy end to the state of siege occasioned by the calamity of this evening.

Thursday, June 16, 2016

Zoo Review: WCS Central Park Zoo

When people talk about "the New York City Zoo", they most often mean the Bronx Zoo, the flagship facility of the world renowned Wildlife Conservation Society. The Bronx isn't the only zoo in New York City, however - it's not even the oldest. That honor belongs to the much smaller Central Park Zoo, found on the island of Manhattan.

Located behind the city's old Arsenal Building, the Central Park Zoo rivals Philadelphia Zoo and Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo for the title of America's oldest. Like many zoos, its origins are murky - enough animals collected at a certain location, most of them cast-off exotic pets, until someone was forced to do something with them, and a zoo was born. Although the zoo housed gorillas and elephants and lions over the years, its real history began in the late 1980s when the City finally became embarrassed of the dilapidated conditions at the zoo, along with the other small zoos scattered across the boroughs. In order to improve things, the authorities of the Bronx Zoo were asked to assume the responsibility of renovating and managing the Central Park Zoo, along with the Queens Zoo and Prospect Park Zoo. They rose to the task magnificently.

Most of the bigger animals are gone from Central Park Zoo, as one would expect from a facility six acres in size. Some, like Pattycake, the gorilla, were relocated to the Bronx Zoo itself. The entire campus was redivided into three zones - Polar, Temperate, and Tropical - a thematic arrangement which remains to this day. (For a more detailed history of the zoos of New York, see William Bridges' Gathering of Animals, or Peter Brazaitis' You Belong In A Zoo! for a history of the early days of the new Central Park Zoo).

The indoor Tropic Zone building is the nucleus of the zoo's bird and reptile collections; visitors walk through a free-flight aviary, where crowned pigeons, Bali mynahs, green peafowl, and other tropical birds fly free. Side exhibits on the ground floor house fruit bats, saki monkeys, and black-and-white ruffed lemurs. Upstairs is a small, treehouse like gallery with viewing of small reptiles, as well as a few small mammals (including rarely exhibiting cloud rat).

On the opposite side of the zoo is the polar area. The zoo's second indoor exhibit building is dedicated to sea birds. One side of the darkened hallway is a long habitat of Antarctic penguins - most notably towering kings, the second largest of the penguins - while puffins are found on the opposite sides. Both habitats feature underwater viewing. A pool of harbor seals and a Eurasian eagle owl are outside. After the zoo's transition under WCS, the largest animals left in the zoo were polar bears, which occupied their outdoor exhibit (complete with underwater viewing) for most of the zoo's recent history. The polar bear exhibit is now currently inhabited by grizzly bears - the pool level has been dropped to provide more land-space for the grizzlies. It can be challenging to take an exhibit that was custom made for one species and modify it for another, but I was pretty surprised at home well it worked in this case with just a simple touch.

Linking the polar and tropical regions is, fittingly enough, the Temperate Territory, which focuses on East Asian species. Japanese macaques (also known as snow monkeys) inhabit an island exhibit, while red pandas frolic in the trees. Muntjac and white-naped cranes are also found here, as is the zoo's newest exhibit, for snow leopards, the first big cats at the Central Park Zoo since its reopening. Across from the snow leopards is one of the most gorgeous waterfowl aviaries I've ever seen, featuring some rarely exhibited sea ducks - long-tails, red-breasted mergansers, and harlequins - as well as pheasants and storks. At the center of the zoo is its most iconic exhibit, the old sea lion pool - a renovated holdover from the old days.

A small petting zoo - formerly a separate component from the old zoo - is nearby. I almost skipped it, running short of time and not being that interested in goats and cattle. I'm glad I didn't, though - it also features a beautiful waterfowl aviary and a handsome family of Patagonian cavies.

Central Park Zoo has been given a gift that few other zoos have been fortunate to receive - a chance to completely reinvent itself as a better facility. It's amazed me over the years how iconic this zoo has been in American pop-culture, largely due to its location. It's been featured in The Catcher in the Rye and Breakfast at Tiffany's, made cameo appearances in TV shows (I recently watched an episode of Law and Order: SVU that showed the detectives interviewing a witness while watching the sea lions), been in comic books (Marvel Comics' vigilante The Punisher once famously fed a mobster to the polar bears), and served as a setting for movies. Some of these movies, like the Madagascar movies, of course feature animals that the zoo hasn't exhibited for decades - lions, zebras, giraffes, hippos - but no one ever accused Hollywood of realism.

All of this is rather amusing for a zoo that's so small and features so few animals, albeit in very attractive enclosures. Perhaps that is because, unlike the Bronx Zoo, located at the edge of the city, Central Park is in the heart of Manhattan - as you walk the zoo, the skyscrapers of America's biggest city form an imposing backdrop. It just goes to show, what they say is true- location, location, location...

Located behind the city's old Arsenal Building, the Central Park Zoo rivals Philadelphia Zoo and Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo for the title of America's oldest. Like many zoos, its origins are murky - enough animals collected at a certain location, most of them cast-off exotic pets, until someone was forced to do something with them, and a zoo was born. Although the zoo housed gorillas and elephants and lions over the years, its real history began in the late 1980s when the City finally became embarrassed of the dilapidated conditions at the zoo, along with the other small zoos scattered across the boroughs. In order to improve things, the authorities of the Bronx Zoo were asked to assume the responsibility of renovating and managing the Central Park Zoo, along with the Queens Zoo and Prospect Park Zoo. They rose to the task magnificently.

The indoor Tropic Zone building is the nucleus of the zoo's bird and reptile collections; visitors walk through a free-flight aviary, where crowned pigeons, Bali mynahs, green peafowl, and other tropical birds fly free. Side exhibits on the ground floor house fruit bats, saki monkeys, and black-and-white ruffed lemurs. Upstairs is a small, treehouse like gallery with viewing of small reptiles, as well as a few small mammals (including rarely exhibiting cloud rat).

On the opposite side of the zoo is the polar area. The zoo's second indoor exhibit building is dedicated to sea birds. One side of the darkened hallway is a long habitat of Antarctic penguins - most notably towering kings, the second largest of the penguins - while puffins are found on the opposite sides. Both habitats feature underwater viewing. A pool of harbor seals and a Eurasian eagle owl are outside. After the zoo's transition under WCS, the largest animals left in the zoo were polar bears, which occupied their outdoor exhibit (complete with underwater viewing) for most of the zoo's recent history. The polar bear exhibit is now currently inhabited by grizzly bears - the pool level has been dropped to provide more land-space for the grizzlies. It can be challenging to take an exhibit that was custom made for one species and modify it for another, but I was pretty surprised at home well it worked in this case with just a simple touch.

Linking the polar and tropical regions is, fittingly enough, the Temperate Territory, which focuses on East Asian species. Japanese macaques (also known as snow monkeys) inhabit an island exhibit, while red pandas frolic in the trees. Muntjac and white-naped cranes are also found here, as is the zoo's newest exhibit, for snow leopards, the first big cats at the Central Park Zoo since its reopening. Across from the snow leopards is one of the most gorgeous waterfowl aviaries I've ever seen, featuring some rarely exhibited sea ducks - long-tails, red-breasted mergansers, and harlequins - as well as pheasants and storks. At the center of the zoo is its most iconic exhibit, the old sea lion pool - a renovated holdover from the old days.

A small petting zoo - formerly a separate component from the old zoo - is nearby. I almost skipped it, running short of time and not being that interested in goats and cattle. I'm glad I didn't, though - it also features a beautiful waterfowl aviary and a handsome family of Patagonian cavies.

Central Park Zoo has been given a gift that few other zoos have been fortunate to receive - a chance to completely reinvent itself as a better facility. It's amazed me over the years how iconic this zoo has been in American pop-culture, largely due to its location. It's been featured in The Catcher in the Rye and Breakfast at Tiffany's, made cameo appearances in TV shows (I recently watched an episode of Law and Order: SVU that showed the detectives interviewing a witness while watching the sea lions), been in comic books (Marvel Comics' vigilante The Punisher once famously fed a mobster to the polar bears), and served as a setting for movies. Some of these movies, like the Madagascar movies, of course feature animals that the zoo hasn't exhibited for decades - lions, zebras, giraffes, hippos - but no one ever accused Hollywood of realism.

All of this is rather amusing for a zoo that's so small and features so few animals, albeit in very attractive enclosures. Perhaps that is because, unlike the Bronx Zoo, located at the edge of the city, Central Park is in the heart of Manhattan - as you walk the zoo, the skyscrapers of America's biggest city form an imposing backdrop. It just goes to show, what they say is true- location, location, location...

Wednesday, June 15, 2016

National Aquarium, Get Your Priorities Straight!

Earlier this week, the National Aquarium in Baltimore announced that, by 2020, it would be phasing out it's Atlantic bottlenosed dolphins, sending the eight marine mammals away. The dolphins would be going to a new, specially built sanctuary, which the aquarium will, in the years to come, be designing, building, and maintaining for the remainder of these animals' lives.

I am so disappointed.

Not that they are phasing out dolphins. I can understand why, even if I don't agree. There's been a lot of public opposition to cetaceans living in human care, and if the National Aquarium doesn't want to deal with that mess anymore, I can respect that, especially if they want to make the argument that they'd rather focus their efforts on conservation.

That's the part of this that makes no sense to me.

They are going to spend how much money - millions, I am guessing - to do this... for eight animals? Eight animals, of a non-endangered species, who, to be pretty frank, are ok where they are now? You don't want dolphins anymore, fine, stop breeding them (which the aquarium has already done). Send them to another facility. That's fine. But spending all of this money and time and effort doesn't strike me as what's best for marine conservation. It strikes me as pandering, of patting yourself on the back for the crowds.

Just last week we heard in the news about the vaquita, and how it's numbers have gotten so critically low that captive breeding may be its only hope. And yet no one is talking about them, or what all of this money could do for their conservation. It could very well be what turns the tide for the species.

The National Aquarium in Baltimore was the first aquarium I ever visited, and it has always meant a lot to me. Over its thirty-odd year history, has done tremendous good for marine conservation, which I respect them greatly for. Which is why this last decision I find so very disappointing.

I am so disappointed.

Not that they are phasing out dolphins. I can understand why, even if I don't agree. There's been a lot of public opposition to cetaceans living in human care, and if the National Aquarium doesn't want to deal with that mess anymore, I can respect that, especially if they want to make the argument that they'd rather focus their efforts on conservation.

That's the part of this that makes no sense to me.

They are going to spend how much money - millions, I am guessing - to do this... for eight animals? Eight animals, of a non-endangered species, who, to be pretty frank, are ok where they are now? You don't want dolphins anymore, fine, stop breeding them (which the aquarium has already done). Send them to another facility. That's fine. But spending all of this money and time and effort doesn't strike me as what's best for marine conservation. It strikes me as pandering, of patting yourself on the back for the crowds.

Just last week we heard in the news about the vaquita, and how it's numbers have gotten so critically low that captive breeding may be its only hope. And yet no one is talking about them, or what all of this money could do for their conservation. It could very well be what turns the tide for the species.

The National Aquarium in Baltimore was the first aquarium I ever visited, and it has always meant a lot to me. Over its thirty-odd year history, has done tremendous good for marine conservation, which I respect them greatly for. Which is why this last decision I find so very disappointing.

Monday, June 13, 2016

From the News: St. Augustine Alligator Farm becomes first U.S. zoo to breed endangered Indian gharial

St. Augustine Alligator Farm becomes first U.S. zoo to breed endangered Indian gharial

Oh, this news is bigger than the headline

suggests. You see, because while gharials have been hatched out in

captivity in their native Nepal and India (where they are used in

reintroduction programs), this marks the first ever hatching of this species of

highly-endangered crocodilian anywhere outside of their native range countries.

You could think of

gharials as being like the pandas of the reptile world. Like pandas, only

a tiny handful of zoos display them. Like pandas, they are a taxonomic

oddity, distinct from their closest relatives in behavior and anatomy.

And like pandas, they are endangered... though gharials are the more

endangered of the two.

When I visited St. Augustine for the first time, some of

their reptile keepers were describing to me the set-up that they were hoping to

use to coax their gharials into breeding. I'm glad to see that their

plans were met with success. Hopefully, this will be the first of many,

and captive-bred gharials from the US can be used to supplement the wild

populations of India and Nepal.

Saturday, June 11, 2016

Last Chance for the Sea Panda

Last year, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums rolled out a new conservation initiative - Saving Animals From Extinction, which, aptly enough, spells SAFE. SAFE was meant to be an integration of zoo and aquarium work combined with field-based conservation. Ten species (or groups of species) were selected to be the trail candidates. These included such iconic zoo and aquarium species as the Asian elephant, the black rhinoceros, and the cheetah, as well as lesser-known animals, like the western pond turtle.

There was also the vaquita, which was strange to me, seeing as there are no vaquita in captivity; AZA's commitment has largely been limited to fundraising, awareness, and supporting scientists' research.

It's entirely possible that this may change.

A dead vaquita in San Felipe photographed in 1992. The vaquita’s facial markings have led it to be labeled the ‘panda of the sea.’ Photograph: Omar Vidal/Reuters

TL;DR Version: The status of the vaquita - an adorable little porpoise found only off the coast of Mexico - has become so precarious that scientists are now forced to consider the possibility of capturing them (there are about 60 left in the world) to form an emergency captive-breeding program, either at aquariums or in sea pens.

The challenges are very real. No one has ever maintained this species in captivity, and when you keep an animal for the first time ever, there is bound to be some trial and error with diet, veterinary care, and other husbandry parameters. Critics of the suggestions (because to be honest, it's not a plan now... barely a concept, even) say that it's too risky. I can understand where they are coming from...

however... this wouldn't be so risky if maybe we had all agreed to try the captive breeding approach before we got down to 60 animals. That's what drives me crazy about these last-ditch captive-breeding programs... people wait until the last minute, putting it off for as long as possible, wait until the animal is three-feet (for a quadraped, anyway) in the grave, and then finally consent to it. Considering the odds zoos and aquariums and other breeding facilities face in those cases, it's a miracle that anything ever gets saved. On the terrestrial side, I suspect we'll be in the same boat with the saola in another few years.

The time to start saving an endangered species is before it almost goes extinct. Hell, the best time to start is before it even becomes endangered. When zoos first began working with African penguins (also a SAFE species), they were extremely common. Now they are endangered - but all of the husbandry knowledge that zoos and aquariums have gained over the years means that the captive population is thriving while the wild one has plummeted. Because we have lots of penguins in zoos, reintroduction may be an option some day... if the mess in the wild ever gets sorted out.

So if you're scared of risking vaquitas, which is understandable, here's what you do. Get yourself the most common porpoise species you can as a surrogate for the vaquita and go through the motions with them - rearing, breeding, feeding, treating - and work out the kinks there. That's what happened with the black-footed ferret recovery project - zoos used European polecats as models.

It almost makes you think that some of the Animal Rights' groups would appreciate all of the work that SeaWorld has done over the years learning about how to maintain and breed various cetaceans in captivity... not that anyone will thank them.

Of course, better do it quickly. Because if there are 60 vaquitas now, who knows what the number will be if anyone finally gets up an makes the decision to do a captive-breeding program. It probably won't be more that 60...

Sure, doing something in this case is very risky. But it might not be nearly as risky as doing nothing.

There was also the vaquita, which was strange to me, seeing as there are no vaquita in captivity; AZA's commitment has largely been limited to fundraising, awareness, and supporting scientists' research.

It's entirely possible that this may change.

A dead vaquita in San Felipe photographed in 1992. The vaquita’s facial markings have led it to be labeled the ‘panda of the sea.’ Photograph: Omar Vidal/Reuters

TL;DR Version: The status of the vaquita - an adorable little porpoise found only off the coast of Mexico - has become so precarious that scientists are now forced to consider the possibility of capturing them (there are about 60 left in the world) to form an emergency captive-breeding program, either at aquariums or in sea pens.

The challenges are very real. No one has ever maintained this species in captivity, and when you keep an animal for the first time ever, there is bound to be some trial and error with diet, veterinary care, and other husbandry parameters. Critics of the suggestions (because to be honest, it's not a plan now... barely a concept, even) say that it's too risky. I can understand where they are coming from...

however... this wouldn't be so risky if maybe we had all agreed to try the captive breeding approach before we got down to 60 animals. That's what drives me crazy about these last-ditch captive-breeding programs... people wait until the last minute, putting it off for as long as possible, wait until the animal is three-feet (for a quadraped, anyway) in the grave, and then finally consent to it. Considering the odds zoos and aquariums and other breeding facilities face in those cases, it's a miracle that anything ever gets saved. On the terrestrial side, I suspect we'll be in the same boat with the saola in another few years.

The time to start saving an endangered species is before it almost goes extinct. Hell, the best time to start is before it even becomes endangered. When zoos first began working with African penguins (also a SAFE species), they were extremely common. Now they are endangered - but all of the husbandry knowledge that zoos and aquariums have gained over the years means that the captive population is thriving while the wild one has plummeted. Because we have lots of penguins in zoos, reintroduction may be an option some day... if the mess in the wild ever gets sorted out.

So if you're scared of risking vaquitas, which is understandable, here's what you do. Get yourself the most common porpoise species you can as a surrogate for the vaquita and go through the motions with them - rearing, breeding, feeding, treating - and work out the kinks there. That's what happened with the black-footed ferret recovery project - zoos used European polecats as models.

It almost makes you think that some of the Animal Rights' groups would appreciate all of the work that SeaWorld has done over the years learning about how to maintain and breed various cetaceans in captivity... not that anyone will thank them.

Of course, better do it quickly. Because if there are 60 vaquitas now, who knows what the number will be if anyone finally gets up an makes the decision to do a captive-breeding program. It probably won't be more that 60...

Sure, doing something in this case is very risky. But it might not be nearly as risky as doing nothing.

Friday, June 10, 2016

Wednesday, June 8, 2016

If You Find a Baby Bird...

I was working this past weekend, which - being a beautiful late spring day - meant that I spent no time at my desk. Then, I was off on Monday and Tuesday. When I got back to the zoo this morning, I wasn't the least bit surprised to find that I had about thirty messages on the zoo phone to answer. Not for me personally, just for "a keeper." Excluding all of the hang-ups, they all tend to fall into two categories.

There are people who want us to take in their pet parrot/tortoise/python/etc. And then there are the people who find baby birds. Once or twice a week there's a fawn too, but mostly it's the birds.

"Baby birds" (and you'll see why I put that in quotations later) are one of the great frustrations of working with animals. That's because the right thing to do is, for once in life, the easiest. Nothing. But people seldom do the right thing. They want to do something.

The vast majority of the time, the baby bird in question is actually a feather-covered fledgling. These are the awkward kids of the bird world, just learning to fly and, like kids first learning to drive, doing it badly. Often they fall out of the nest on that maiden flight and then just sit there, looking kind of dumb. That's ok. That's what they are supposed to do. It's how they learn. They can't learn, however, if they get scooped up in a shoebox and taken home by someone who means well but doesn't know what they are doing. The best thing to do is put it somewhere safe nearby, like a bush, out of danger where it can prepare to try again at its own pace.

If it is an actual baby - naked, incapable of perching - try finding the nest and put it back. Ignore the old adages about "the mom and dad bird will smell your scent on the baby and abandon it" - most birds can't really smell. If the bird is injured, the best thing to do is contact a wildlife rehabilitator to take it in. Those folks know what they are signed up for. You don't. Hand-raising a baby bird (which I've done, and am still recovering from) is exhausting. The younger the bird, the more ravenous the appetite. Sometimes, feedings come at the rate of a few per hour. Hope you're not a deep sleeper.

As for fawns, this is also one of those rare situations where ignoring the problem makes it go away, usually. Most deer are hiders - they leave their young, tender, highly-edible fawns hidden while they go out to feed, knowing that is is safer hidden in deep brush than it is following mom around, exposed to predators. Almost all "abandoned" fawns are likely being watched by their nervous mothers nearby, who are stomping their hooves in frustration that humans have found their young. The best thing to do is leave them be.

None of this is, I have to admit to the panic-filled people I talk with on the phone, is a guarantee that everything will be fine. We can't promise that, five seconds after you turn your back, a fox won't tear down and run off with that fawn, or a snake won't gobble that nestling bird. But the sad truth is, that's perfectly natural as well. What's also a sad truth, however, is that relatively few animals taken in by amateur, unknowledgeable rescuers have happy endings.

As a species, we often feel the drive to act boldly to help those we see as in need. Sometimes, the most helpful thing we can do, however, is walk away and let things be. Sometimes, our help only makes things worse.

For more info, here's a list of FAQs from Cornell University's Lab of Ornithology on the subject

There are people who want us to take in their pet parrot/tortoise/python/etc. And then there are the people who find baby birds. Once or twice a week there's a fawn too, but mostly it's the birds.

"Baby birds" (and you'll see why I put that in quotations later) are one of the great frustrations of working with animals. That's because the right thing to do is, for once in life, the easiest. Nothing. But people seldom do the right thing. They want to do something.

The vast majority of the time, the baby bird in question is actually a feather-covered fledgling. These are the awkward kids of the bird world, just learning to fly and, like kids first learning to drive, doing it badly. Often they fall out of the nest on that maiden flight and then just sit there, looking kind of dumb. That's ok. That's what they are supposed to do. It's how they learn. They can't learn, however, if they get scooped up in a shoebox and taken home by someone who means well but doesn't know what they are doing. The best thing to do is put it somewhere safe nearby, like a bush, out of danger where it can prepare to try again at its own pace.

If it is an actual baby - naked, incapable of perching - try finding the nest and put it back. Ignore the old adages about "the mom and dad bird will smell your scent on the baby and abandon it" - most birds can't really smell. If the bird is injured, the best thing to do is contact a wildlife rehabilitator to take it in. Those folks know what they are signed up for. You don't. Hand-raising a baby bird (which I've done, and am still recovering from) is exhausting. The younger the bird, the more ravenous the appetite. Sometimes, feedings come at the rate of a few per hour. Hope you're not a deep sleeper.

As for fawns, this is also one of those rare situations where ignoring the problem makes it go away, usually. Most deer are hiders - they leave their young, tender, highly-edible fawns hidden while they go out to feed, knowing that is is safer hidden in deep brush than it is following mom around, exposed to predators. Almost all "abandoned" fawns are likely being watched by their nervous mothers nearby, who are stomping their hooves in frustration that humans have found their young. The best thing to do is leave them be.

None of this is, I have to admit to the panic-filled people I talk with on the phone, is a guarantee that everything will be fine. We can't promise that, five seconds after you turn your back, a fox won't tear down and run off with that fawn, or a snake won't gobble that nestling bird. But the sad truth is, that's perfectly natural as well. What's also a sad truth, however, is that relatively few animals taken in by amateur, unknowledgeable rescuers have happy endings.

As a species, we often feel the drive to act boldly to help those we see as in need. Sometimes, the most helpful thing we can do, however, is walk away and let things be. Sometimes, our help only makes things worse.

For more info, here's a list of FAQs from Cornell University's Lab of Ornithology on the subject

Tuesday, June 7, 2016

Species Fact Profile: Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus)

Green Anaconda

Eunectes murinus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Range: Northern South America, Trinidad

Habitat: Flooded Savannahs

Diet: Vertebrates (Size Proportionate to Snake)

Social Grouping: Asocial

Reproduction: Mate during dry season (February-May), multiple females attracted to single female, competing for access. Female gives live birth to 20-40 (but up to 80) offspring, about 60 centimeters long each. Young are independent immediately, reach sexual maturity at 6 years old

Lifespan: 10 Years (Wild), 25-30 Years (Captivity)

Conservation Status: CITES Appendix II

- Generally considered to be the largest (not longest) snake in the world, with lengths of 6-9 meters and weights of up to 200 kilograms. Unverified historic reports and travelers' tales describe snakes of much larger size, but these are unconfirmed.

- Females may be up to five times larger than males, the greatest size difference between the sexes of any terrestrial vertebrate

- Upper-parts are olive green, boldly marked with dark oval spots, which grow smaller on the sides. Head has distinctive stripe running from the eyes to the back of the head, often edged with orange

- Highly aquatic, spends most of its time in the water -eyes and nostrils are positioned at the top of the head to enable the snake to see and smell while mostly underwater

- Will feed on any vertebrate of appropriate size - juveniles eat fish, lizards while adults take animals the size of caiman and capybara. Very large animals could take animals the size of deer or tapir. Attacks on humans have (very rarely) been reported

- Females may occasionally eat males that come to breed with her after mating

- Survive periods of drought by burying themselves in mud and entering state of dormancy; if water is available, they will remain active year-round

- Hunted for skins, meat, and pet trade; also killed by local people fearful of risk of anaconda attacks

- Small feral population has become established in Florida, leading to strict new rules about the importation and interstate movements of anacondas and other large constrictors

- Origin of the name "Anaconda" means "Elephant Killer" in Tamil; the Latin name translates to "Good Swimmer of Mice"

Monday, June 6, 2016

From the News: Penguins evacuated from Utah aquarium

Over the years, there have been some spectacular advances in technology which have made it possible for us to exhibit animals in ways and in places where it never would have been possible years ago. Climate control systems allow polar animals and tropical animals to live in the same latitude. Artificial seawater makes it possible to keep marine animals inland. It's been fascinating to see the advances and improvements over the years.

Of course, we are very much at the mercy of that technology for the survival of our animals in these conditions, as evidenced by the results of Hurricane Katrina at the Aquarium of the Americas. A just as fitting example, but with far less disastrous results, occurred at the Loveland Living Planet Aquarium in Utah recently.

Keeping Antarctic penguins in Utah may seem like a fool's errand, but (usually) it seems to work. When it didn't, it looks like the staff at Loveland were up to the task. No penguins were harmed by the smoke (resulting from faulty air-conditioning), though a few keepers required brief hospitalization due to smoke inhalation. We'll wish them a speedy recovery, as well as thanks for saving the birds.

Sunday, June 5, 2016

Zoo History: A Wonderful Place for Our Zoo

"In my opinion zoological gardens all over the world should have as one of their main objects the establishment of breeding colonies for these rare and endangered species. Then, if it is inevitable that the animal should become extinct in the wild state, at least we have not lost it completely. For many years I had wanted to start a zoo with just such an object in view, and now seemed the ideal moment to begin."

- Gerald Durrell, A Zoo in My Luggage

Every zoo has a history, though in most cases it's a rather simple, formulaic one - enough animals are dumped in a place until someone decides to do something with them. Not every zoo makes history. To celebrate Zoo and Aquarium Month this year, I've decided to start off with the story of a zoo that has undoubtedly changed the world for the better. What makes this all the more remarkable is that its history - which doesn't go very far back - began in the head of an eccentric young man who no one ever thought would amount to much.

Gerald Durrell has appeared before on this blog - way back, I reviewed one of the many books that he'd written over his career, A Bevy of Beasts, a narrative about his apprenticeship as a zookeeper at Whipsnade. Zoos were always a part of Durrell's life; family legend has it that "zoo" was his first word, and some of his first memories were of visiting a zoo in India, where he was born. After leaving Whipsnade, Durrell made his name by traveling the world, collecting animals for zoos back in England and specializing in the obscure (a man after my own heart). Encouraged by his brother, the novelist Lawrence Durrell, he recorded his exploits in a series of highly amusing books, beginning with The Overloaded Ark, describing his first expedition, to Cameroon. The arkload in question included drills, pangolins, dwarf crocodiles, and, perhaps the least-known animal of the region, the lemur-like angwantibo.

Despite Durrell's fondness for zoos, he quickly became disillusioned with them. He was baffled by the inability of zoos, even some of the world's most prestigious, to successfully keep the animals that he himself was able to keep for months at a time in his bush camps. He also felt that there was too much focus on the wrong animals - big, showy species instead of the more endangered but often overlooked ones. His efforts to gain employment at a zoo in England were unsuccessful (even today the zoo world is full of would-be visionaries who swear that they could change the world forever if only someone would let them... I should know, I spent the last ten years as one). Undaunted by this failure, he did - what to him seemed to be - the only logical thing left. He decided to start his own zoo.

Now, if I were in Durrell's position, I would have found a place to establish my zoo, built enclosures, and then acquired animals. Durrell was nothing if not unconventional, though, as zookeepers often are. He returned from another expedition to Cameroon with his load of animals but, instead of selling them to other zoos, began to try and find a place to house them permanently. From chimpanzees to clawed frogs, Gerald Durrell arrived in England with, to borrow the title from one of his books, a zoo in his luggage. Some of the animals were loaned out to other zoos. Some were housed in a local department store as sort of a "preview zoo" (their numbers included a baboon who managed to escape and run amok). Others still were set up in the yard of Gerald's sister, Margo, which did little to endear them to the neighbors. All the while, local council after local council turned their noses up at Durrell's zoo, to his considerable annoyance.

It was a complete fluke that Gerald Durrell met Major Hugh Fraser, proprietor of a rambling 17th century manor on Jersey, one of the Channel Islands between the United Kingdom and France. Meeting Hugh at his home for the first time, Gerald turned to his wife, Jacquie and, in Major Fraser's presence, said "Wouldn't it make a wonderful place for our zoo?" To which the good major replied, "Are you serious?"

Major Fraser wasn't being incredulous (well, maybe a little). It just so happened that the sprawled Les Augres Manor was getting to be too much for him to manage, and he was interested in renting it out. Why not to a zoo? Shortly after, the Jersey Zoo was born.

Jersey Zoo was renamed Durrell WIldlife Trust after the death of its founder, Gerald Durrell, in 1995. To this day, it carries on its founder's dreams of devoting itself to the conservation though captive breeding and reintroduction of the rarest animals on the planet, many of which the world has largely ignored. It operates field stations in countries around the world, from Madagascar to India, and has been very active in the training of range-country naturalists to carry on the struggle of conservation using training and equipment supplied by the Trust. Perhaps most satisfying to Gerald Durrell would be that the conservation mindset that he advocated for in the zoo community decades ago is now embraced and championed by zoos and aquariums around the globe. From a dream no one thought possible has come so much good for so many species around the world.

Friday, June 3, 2016

Zoo and Aquarium Month

Wow... so all of that was very depressing. Moving on from May... it's June, and that means it's Zoo and Aquarium Month! Which would make a lot more sense if National Zookeeper Week was in June, but oh well. It's been a hard month for the zoo community, especially all those affected by the tragedy at Cincinnati Zoo, but we're a resilient bunch. I've heard a lot of positive support for us around the country, and I know that we'll continue to move forward. In the meantime, I hope that everyone has a chance to remember why they joined the most awesome of professions and never has cause to regret it.

Happy Zoo and Aquarium Month!

The awesome illustration below is from Peppermint Narwhal Creative, one of the best animal art sources out there.

Happy Zoo and Aquarium Month!

The awesome illustration below is from Peppermint Narwhal Creative, one of the best animal art sources out there.

Thursday, June 2, 2016

Satire: Zoos to consult internet polls during future emergencies

The nation’s zoos have collectively agreed to a new contingency plan for responding to emergency situations.

The decision comes following days of debate and outrage stemming from

an incident in which a silverback gorilla was shot dead after a young

boy fell into an exhibit.

Charles Finster of the Harvard school of Zoology and sarcasm spoke on behalf of the nation’s zootopians.

“We were arrogant to respond to the situation in such a

hasty manner,” said Finster. “We didn’t even bother to do a basic Google

search. What were we thinking?”

Zoos are advising visitors to pack enough food to last at least a day

so there is enough time to successfully measure the general consensus

before responding.

Visitors are also instructed to refrain from feeding the animals they end up trapped with.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)